This is a presentation I gave to the ORCID Research Integrity Webinar series - an overview of the Researcher Identity Verification framework I’ve been working on.

(The slides were built using Simon Willison’s excellent Annotated Presentation Creator)

Thanks, and hello everyone. I’m going to just dive in.

We’re here to talk about an important subject, but I just want to get briefly philosophical and explain why I think it’s so important, before we connect the dots to the real subject of this talk and work we’ve been doing.

Research integrity is the title of plenty of articles and conference presentations these days, and it sounds like a no-brainer. Integrity is a good thing, so everybody wants it. But I want to unpack this a little bit, to say a bit more about why it matters so much.

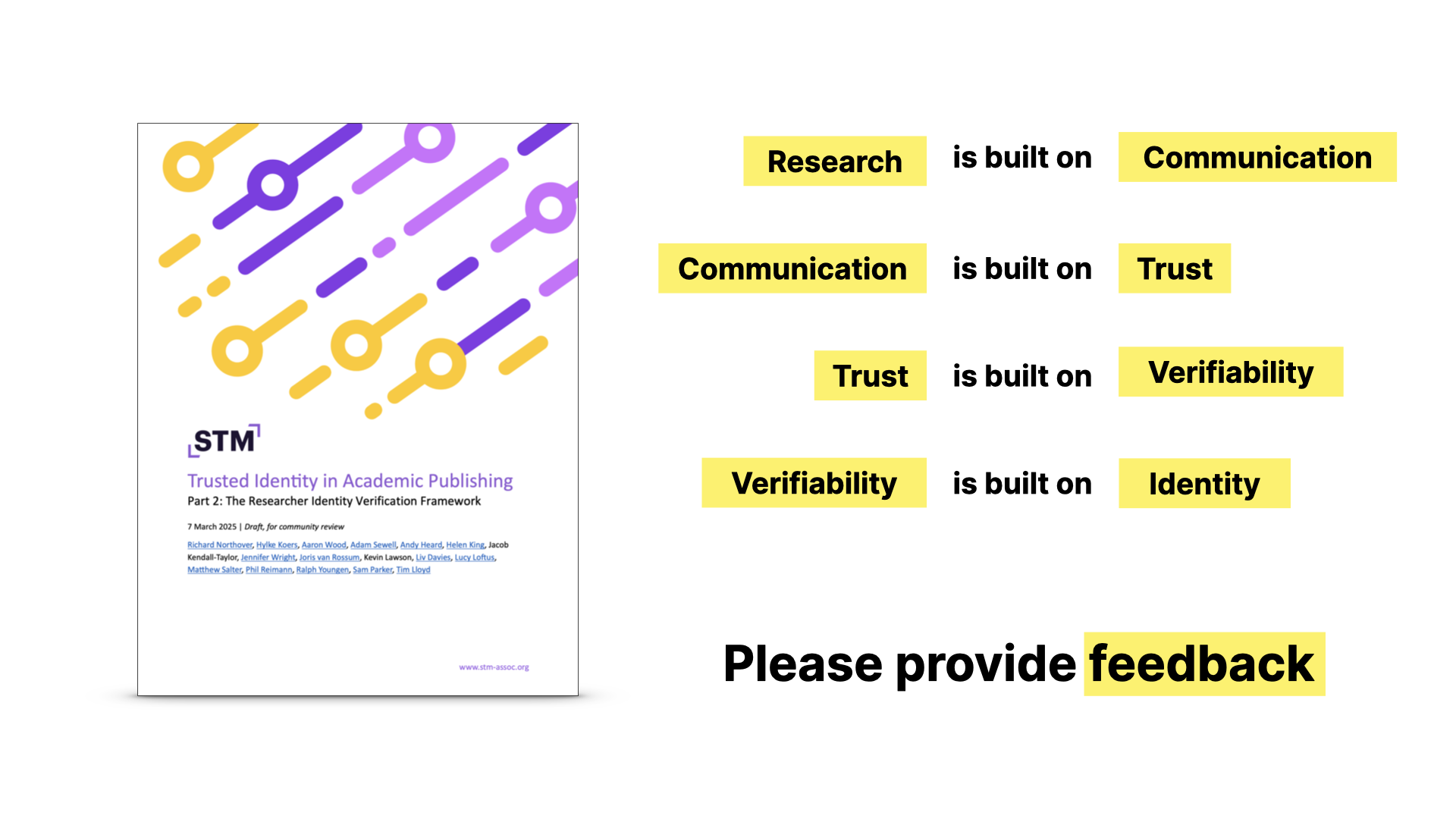

Research is a collective thing. It’s the structured sharing of knowledge. It depends on communication - on sharing ideas, results and questions. It’s about working on the basis of what’s been done before. Communication is, in the end, what science publishing is all about, regardless of the mechanisms and business models that evolve around it.

But for this most fundamental thing to work, for communication to work, there has to be trust. Not blind trust, but the kind of rational human trust that lets us rely on what others say - at least enough to test it, challenge it, build on it.

Effective communication assumes a shared frame of reference and some degree of trust - that what you read isn’t arbitrary or deceptive.

In evolutionary biology and in game theory, this is well understood: communication depends on honest signals. If signals can be faked without cost, they stop conveying information, and become noise. The system breaks down. And so you need a mechanism - something that makes honesty detectable, and balances out dishonesty.

The motto of the Royal Society is in Latin, and it’s nullius in verba which translates to ‘on the word of no-one’ or ‘take nobody’s word for it.’

It sounds like a rejection of trust, but it’s not. It’s actually the opposite. It’s a recognition that trust in science isn’t blind and automatic - it’s about verifiability.

We don’t - and must not - accept things because someone says they’re true - we accept them because we can check them, replicate them, and examine their foundations. That’s what makes trust rational in a scientific context, and it’s what makes science science.

But if there’s a realistic possibility of cheating - and part of that is people being able to misrepresent who they are, make false contributions and hide behind fake claims about themselves and their work - then the whole system breaks down.

We’re no longer working with ideas and results and the work of science - we’re forced to spend time verifying not just the conclusions, but whether the research exists at all.

And to put it bluntly, that’s bad. without these things, there’s less confidence in research. It stops the process of science from working. Instead of building knowledge, we see the undermining of the very things that make it possible.

In research, and in many areas of human life in the real world or the digital one, identity is fundamental.

It’s hard to trust a claim without knowing who made it, or what entity it’s tied to, because the fabric of trust is made up of these connections.

Identity gives accountability, which is what makes communication meaningful. It just needs to be strong enough to establish continuity – so we can say: yes, this person made this claim, and they have acted consistently over time. This is what ORCID is about, you could say.

When we talk about research integrity, and this subject I’m coming on to, researcher identity verification, we’re not talking about it for the sake of it. We’re talking about doing just enough to preserve the basic conditions under which science can happen.

which I think we probably agree is an important thing to communicate about

So this is why we’ve been doing this work on Researcher Identity Verification …which, if you want a catchy name, can be shortened to RIVER.

We’ve spent well over a year working on this, and have produced these two reports, which I’d encourage you to look at if you haven’t already.

They’re the result of discussions in a working group drawn from a wide range of people from various publishers and editorial systems, but - and it’s important to say this - we’re working to get opinions from the whole world of academic publishing, and that’s why I’m here.

So what am I going to talk about?

Broadly, I’m going to take us through the problem…

then introduce the framework that we’ve worked out to try to address the problem.

Then I’ll highlight the main recommendations from the report

…and talk about some of the challenges and work we’re doing to move forward on those.

So what’s the problem?

Firstly, research fraud is increasingly common. There are many papers out there - not fraudulent ones, we trust - that have documented the thousands of retractions due to fake papers making their way into the academic literature.

There are many motivations for this fraud, and those are a subject in their own right…

And as I’ve said, this has some pretty negative consequences.

The next point is that fraud is very often based on identity manipulation. Lots of people act dishonestly in other ways - plagiarism, falsifying results and so on, under their own names - but the growth of paper mills - large-scale efforts to sell fake authorships and get papers into journals of various kinds under false pretences, is fundamentally built on identity manipulation.

it’s often woven together with data fabrication and fake images and other things.

But we’re talking about networks of fake reviewers, fake affiliations, hijacking legitimate researcher identities, and so on. We’ve done some surveys into this, and most people working in this area are familiar with these kinds of tactics.

The thing is, identity manipulation is relatively easy to do, because there’s little or no verification, and the scale of the problem makes it hard to keep up. There’s an arms race, and it’s not a balanced one.

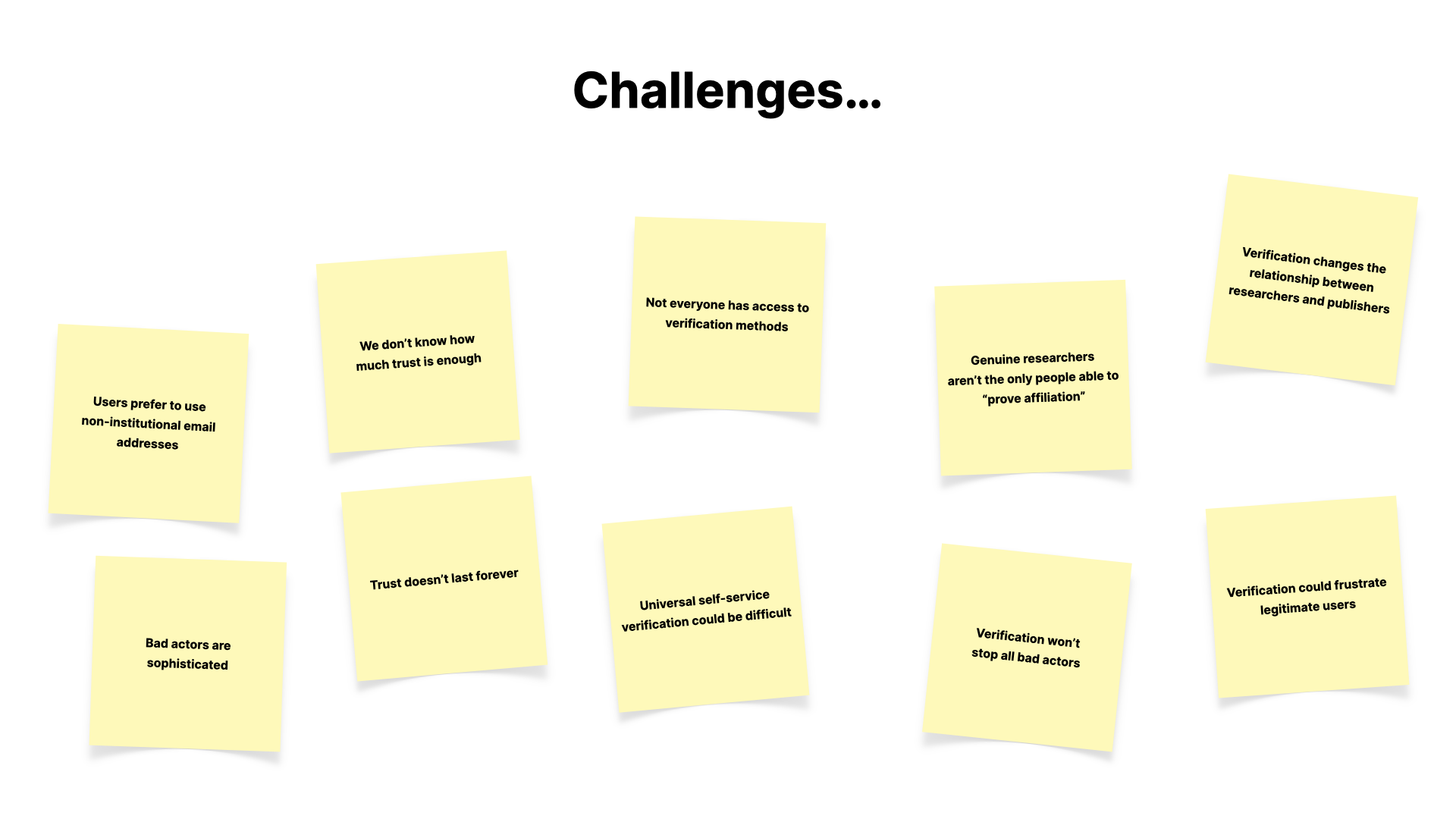

And this is because verification is relatively hard. There’s justified reluctance to put barriers in the way, and the risk of making life more difficult for legitimate researchers, or of excluding them entirely

But what is identity verification? What are we talking about here?

Let’s take a step back and use an example to illustrate.

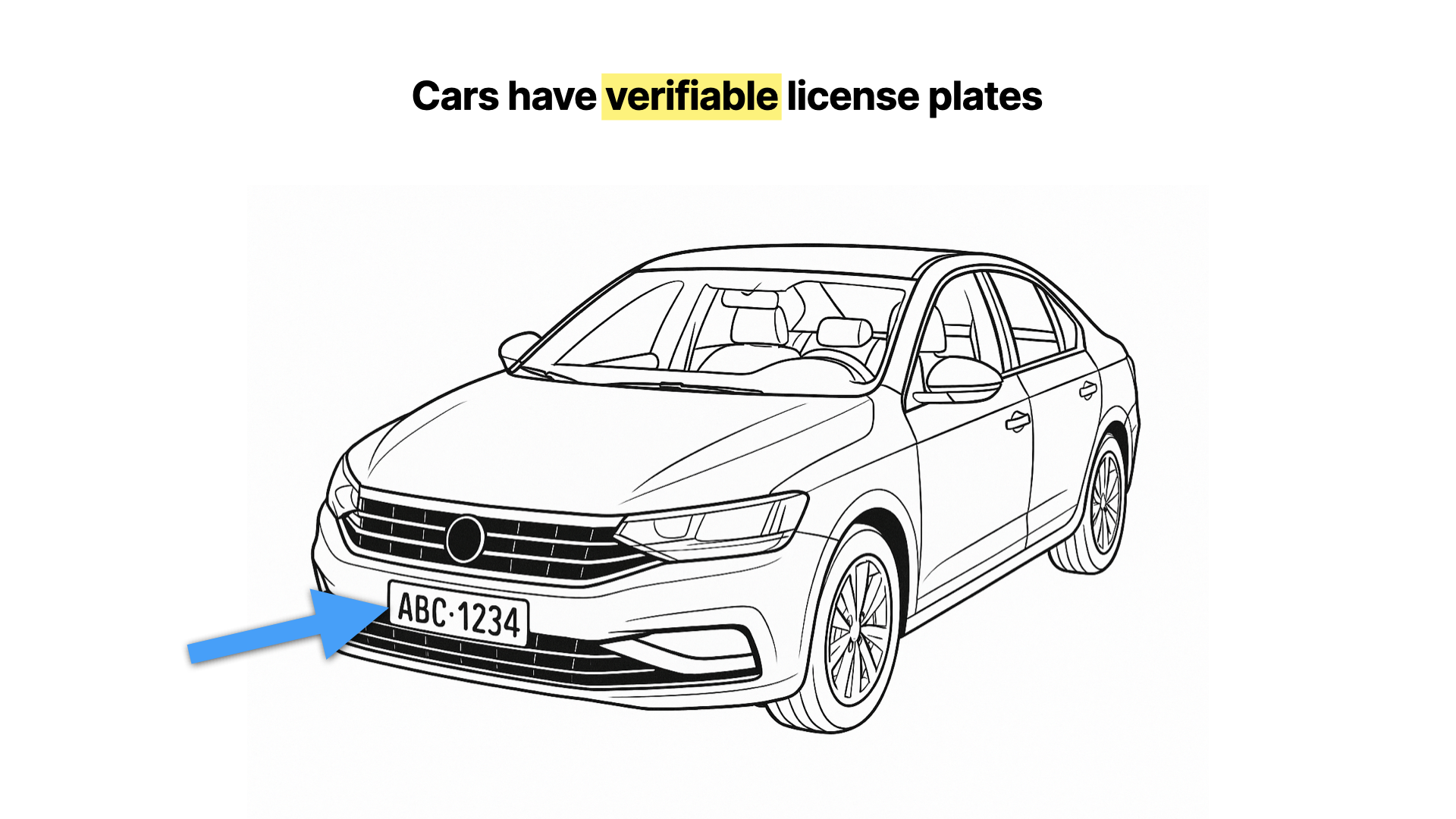

Imagine you’re driving a car. You’re operating a machine that’s powerful, useful - but has consequences if it’s misused. The reason we let cars onto public roads is because there’s a system of accountability: license plates.

License plates don’t reveal your personal identity to everyone - but they allow other parts of the system to link actions to responsible actors when it matters. That’s how a system of trust scales up in a society.

And the system only works if those plates can be verified.

If anyone could draw their own number plate in felt tip pen - or copy someone else’s - the whole thing would collapse.

Your annotation preview will appear here…

Your annotation preview will appear here…

You couldn’t do anything about dangerous drivers. You couldn’t enforce rules. Everyone would be on the road, doing risky things, with no practical way to tell who was accountable.

Unfortunately, that’s exactly how large parts of the academic publishing system currently work.

We have researchers submitting papers, sometimes under fake names, fake affiliations, or email addresses like richard@gmail.com. We have no reliable way of telling who someone really is–or whether they’re even a real researcher. The academic equivalent of a felt-tip license plate.

Now, we could keep going with this metaphor and have a separate conversation about the academic equivalent of a speed camera… but let’s get back to the editorial process.

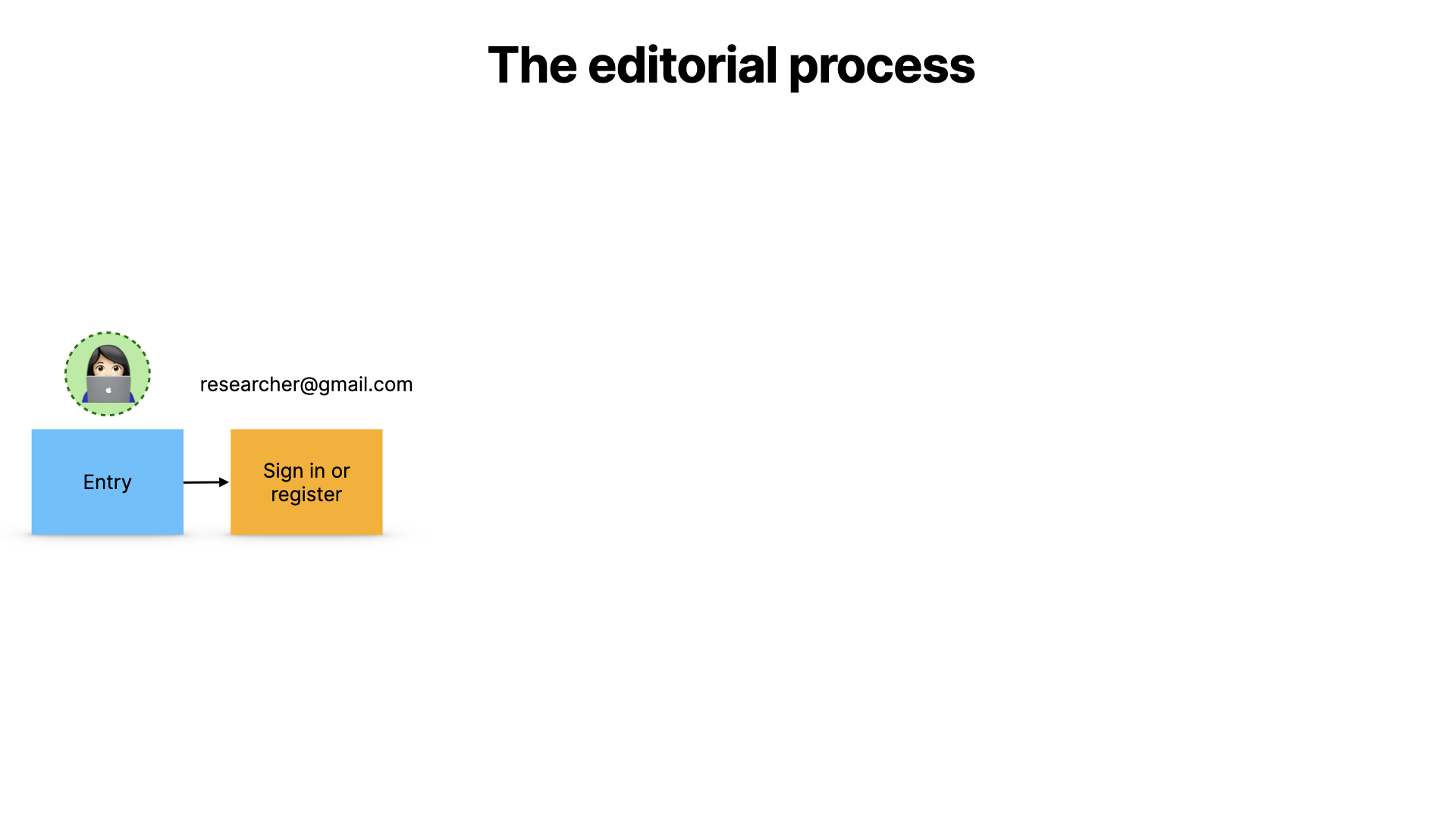

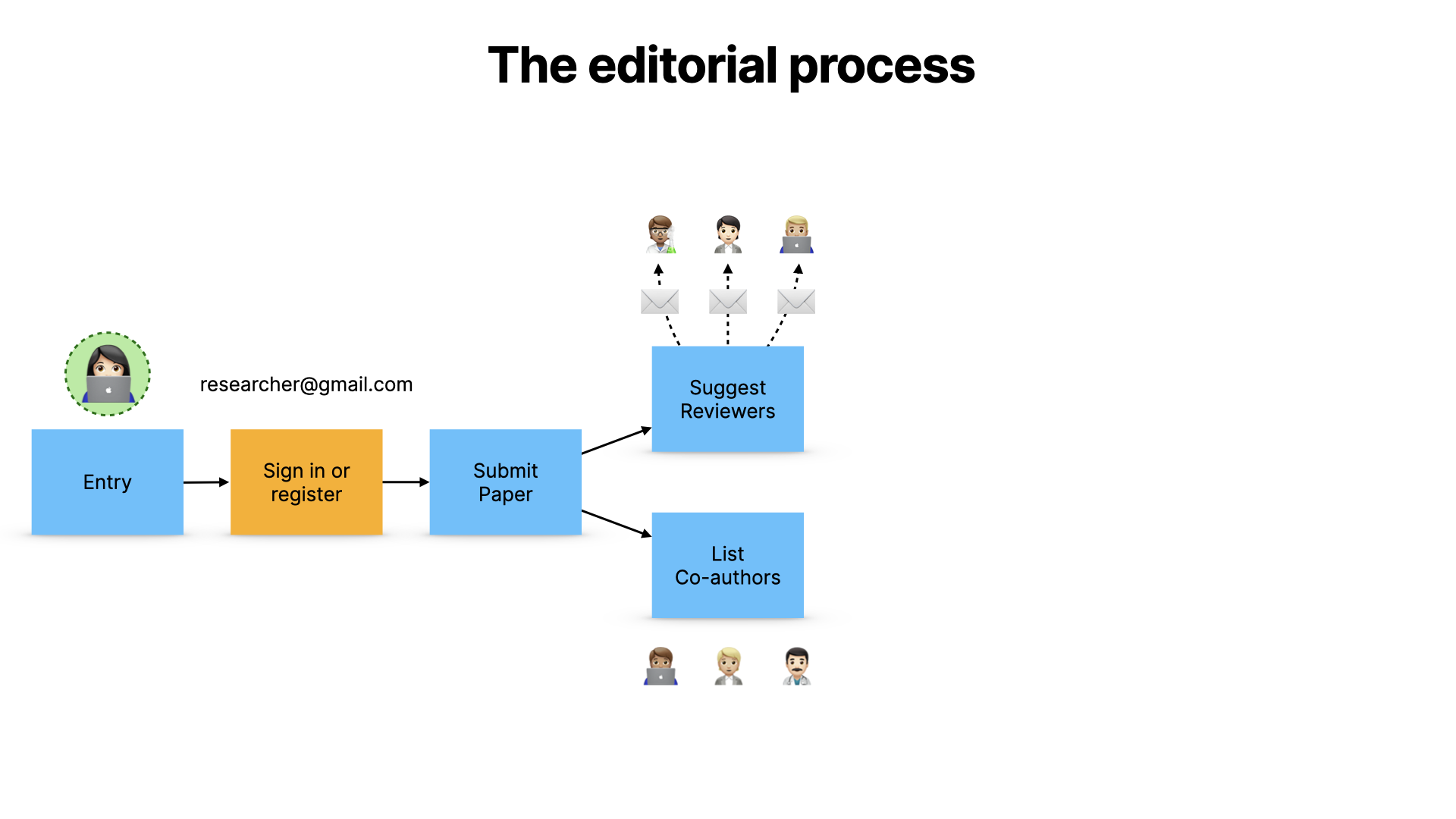

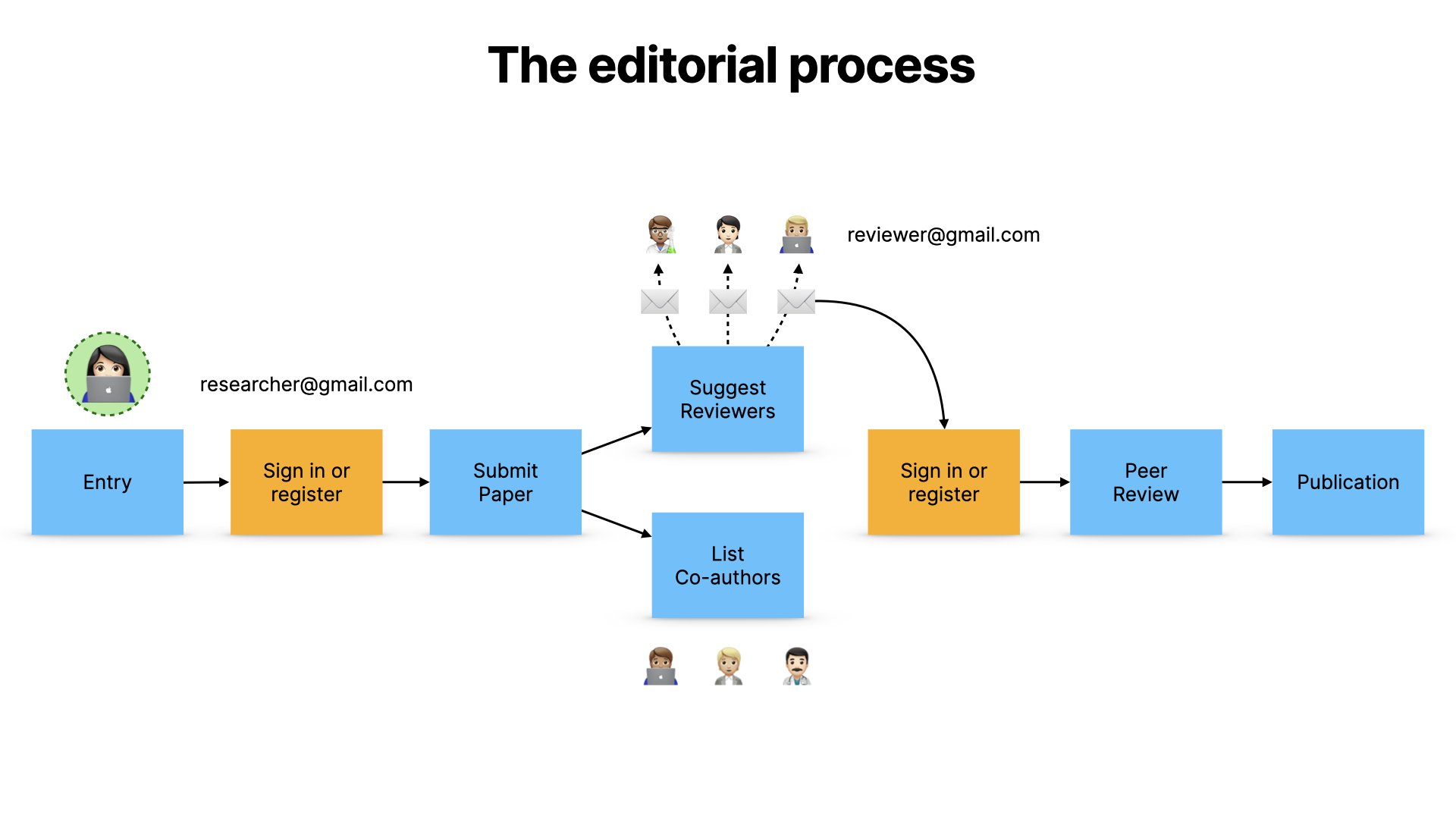

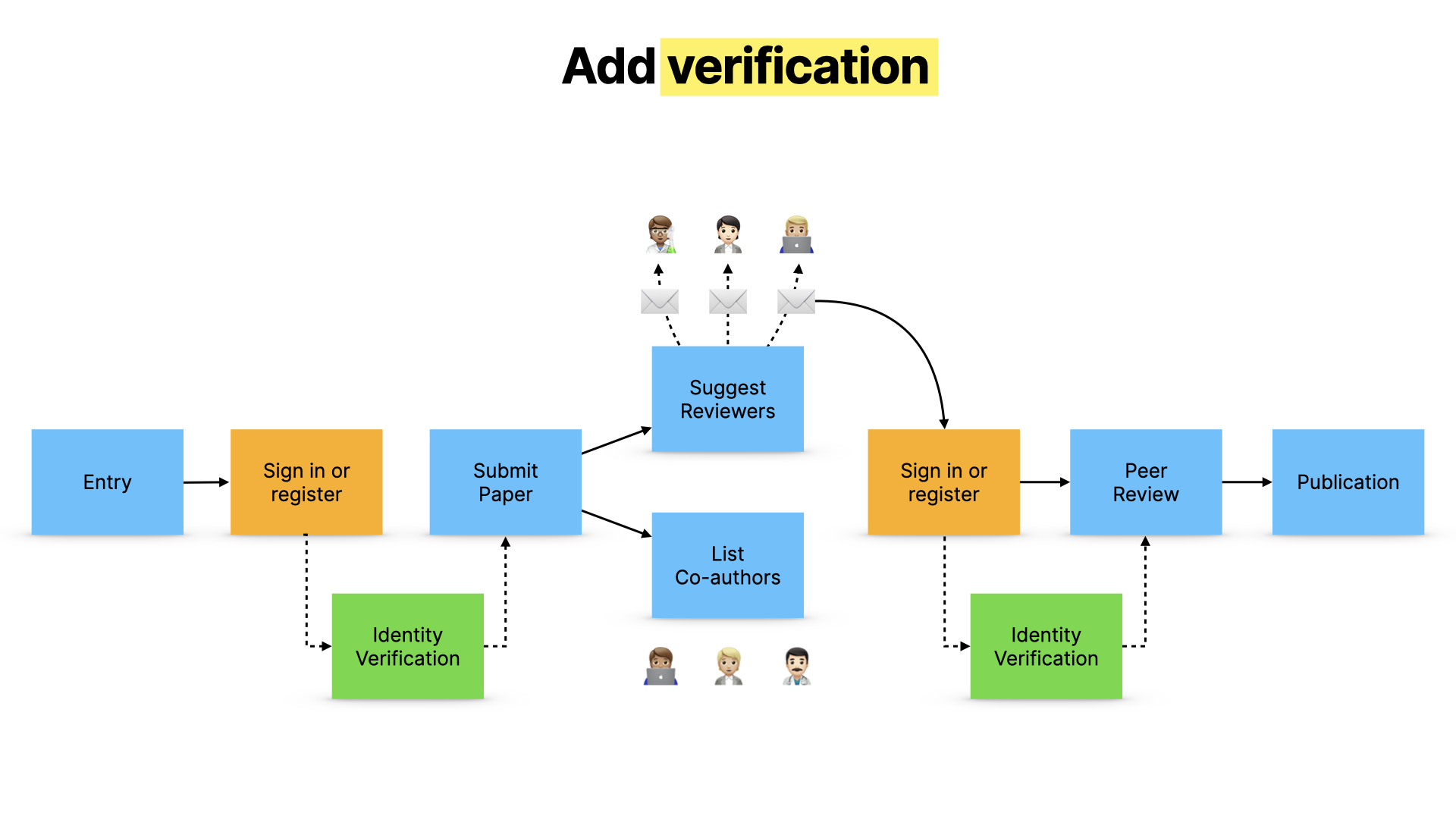

Let me walk you through two simple scenarios. One is going to be honest, and the other isn’t.

The first signs in as they would today, with a personal email address…

…and they submit real work. They list their genuine coauthors, and are asked to suggest genuine reviewers.

Those reviewers are invited to take part in peer review, and they also sign in with their personal email address, and they submit their review, and the paper is published. It’s a simplification, but it’s basically how it works.

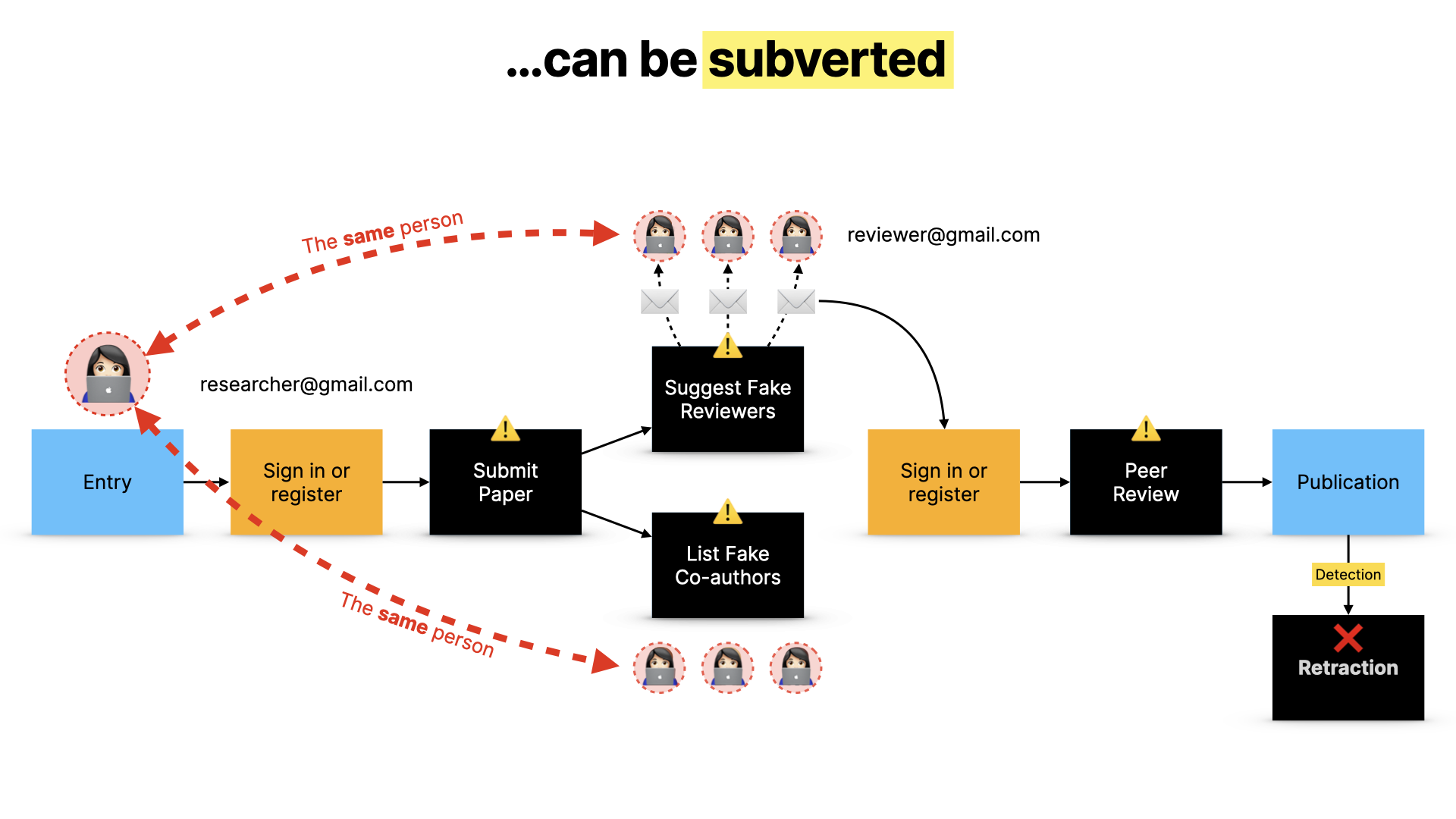

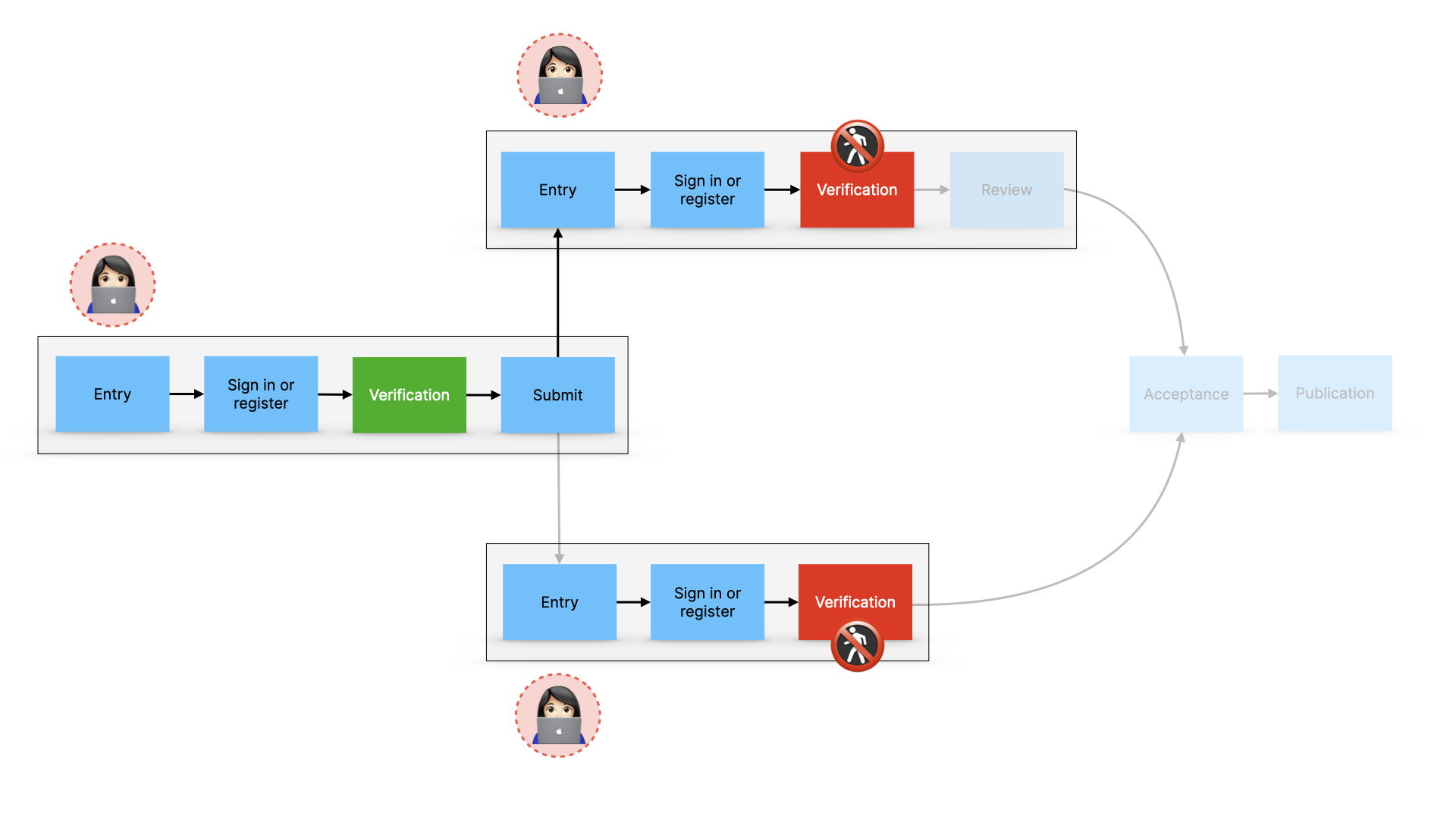

The problem is that this can be subverted.

- The bad actor submits fake work, fake co-authors, fake reviewers - but all these users are the same person, who's able to review their own paper

- And it works

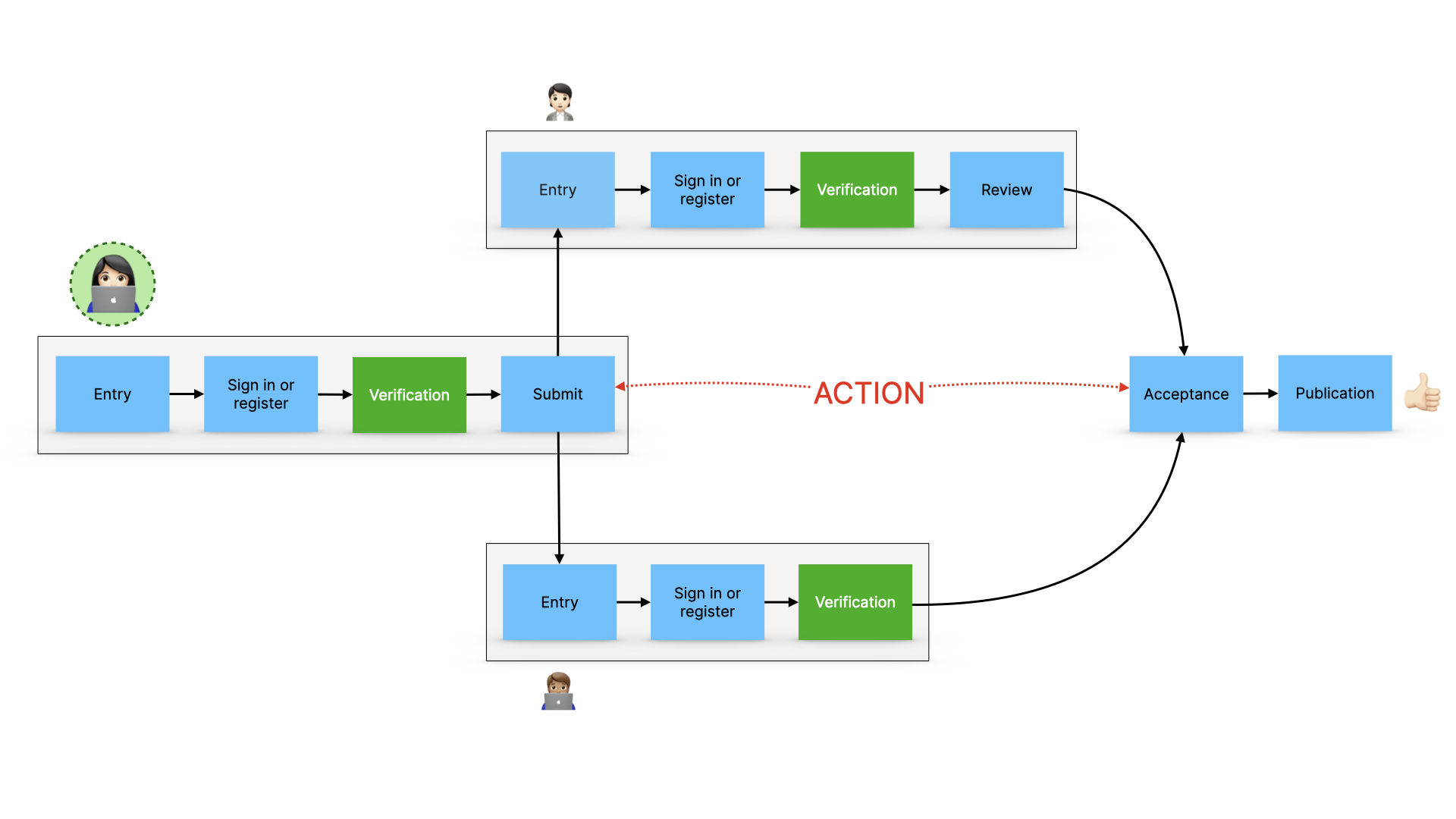

The answer is verification.

But the big question is how?

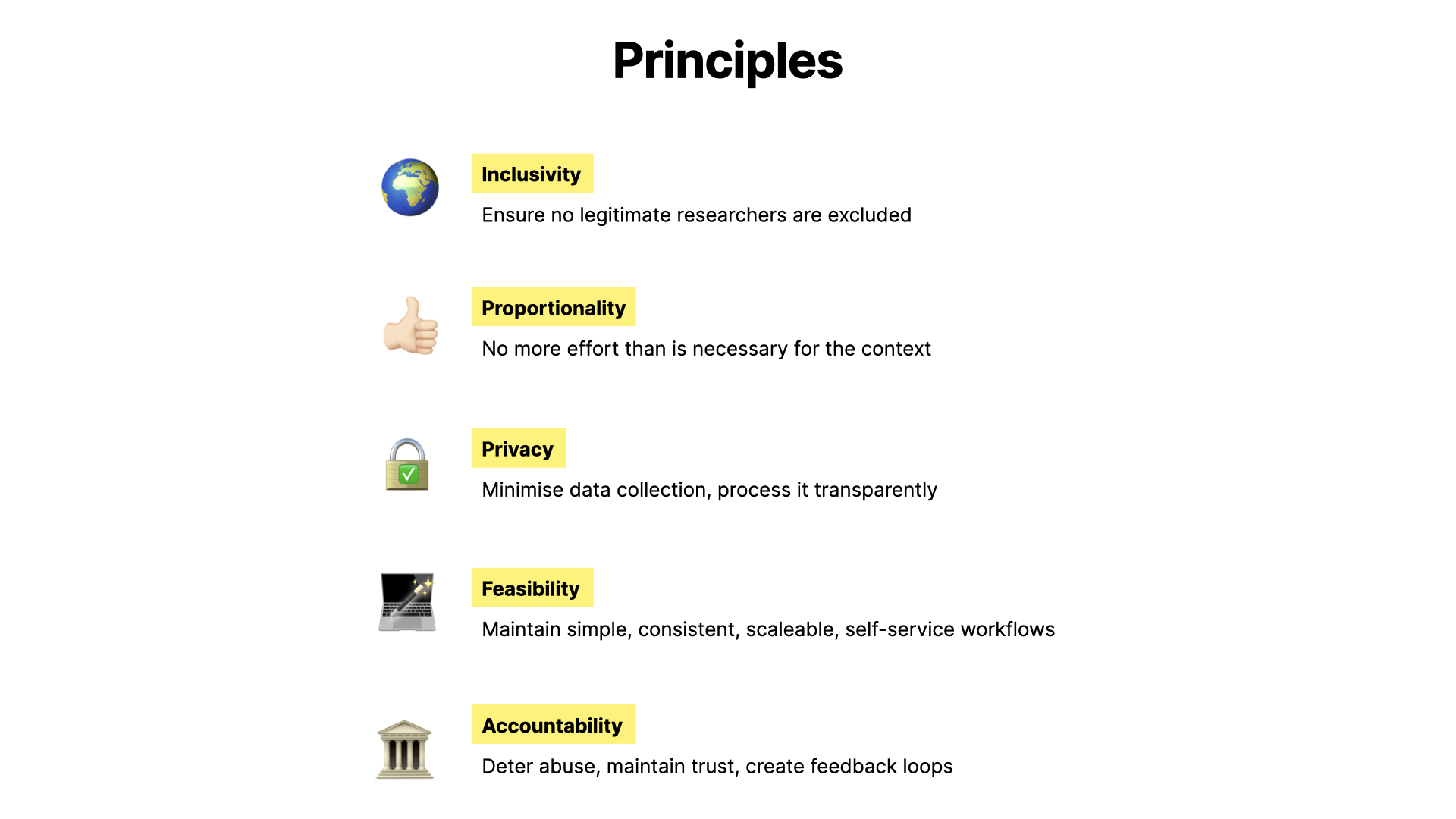

So we need to step back and think about what the principles of our approach should be. The report goes into this in lots of detail, but in summary:

- We need to make sure that verification doesn't exclude people

- We need to make sure that it's proportional, and not asking for more or requiring more effort than is necessary

- Related to this, we need to make sure that it's minimising data collection, and handling it properly

- The whole process has to be possible to implement, and has to actually work in real life

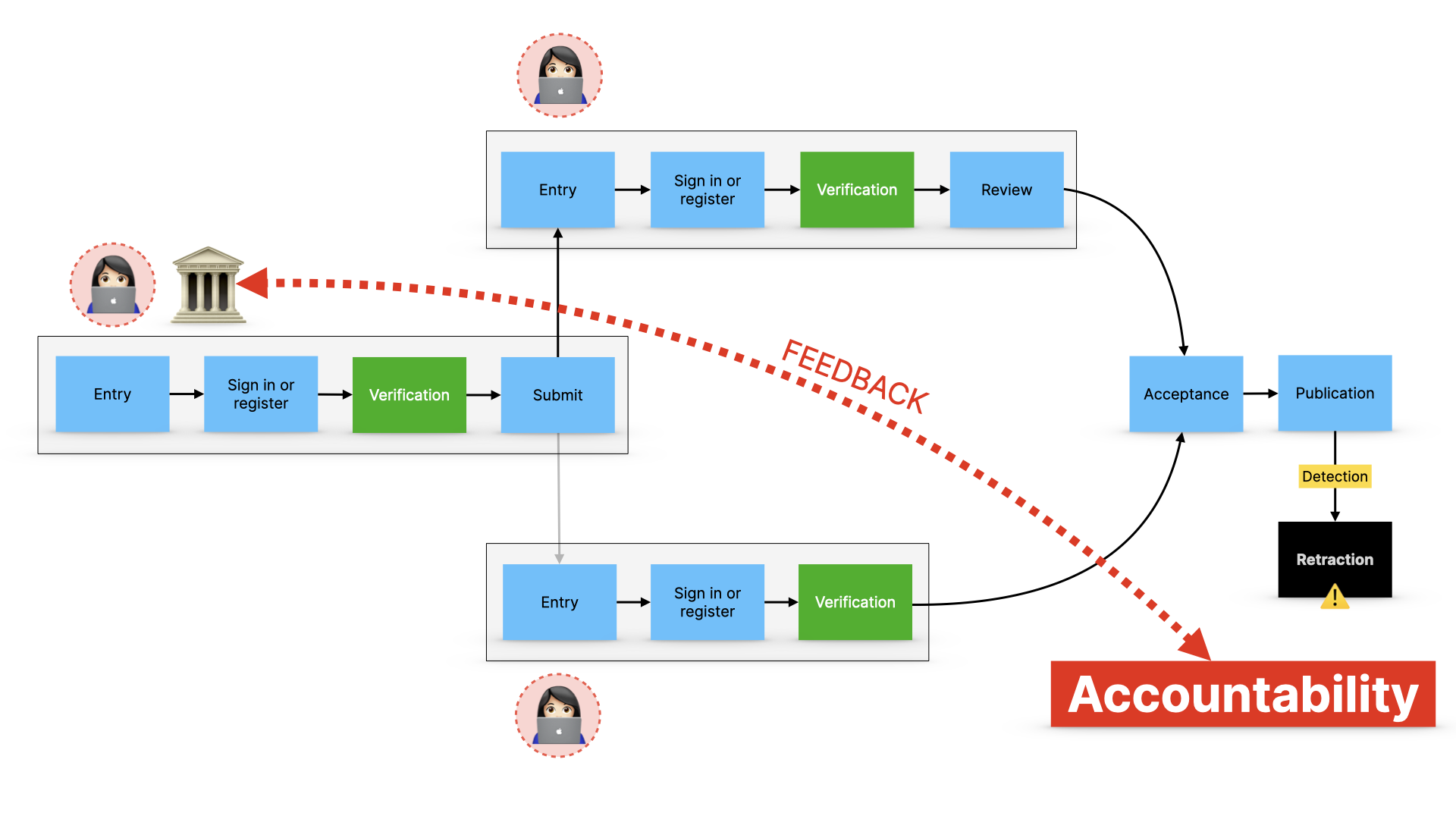

- And it has to work as a larger system, making it possible to set up accountability loops, a bit like the drivers licence example.

And this is where the framework comes in: it’s an effort to describe a way to introduce identity verification in line with these principles.

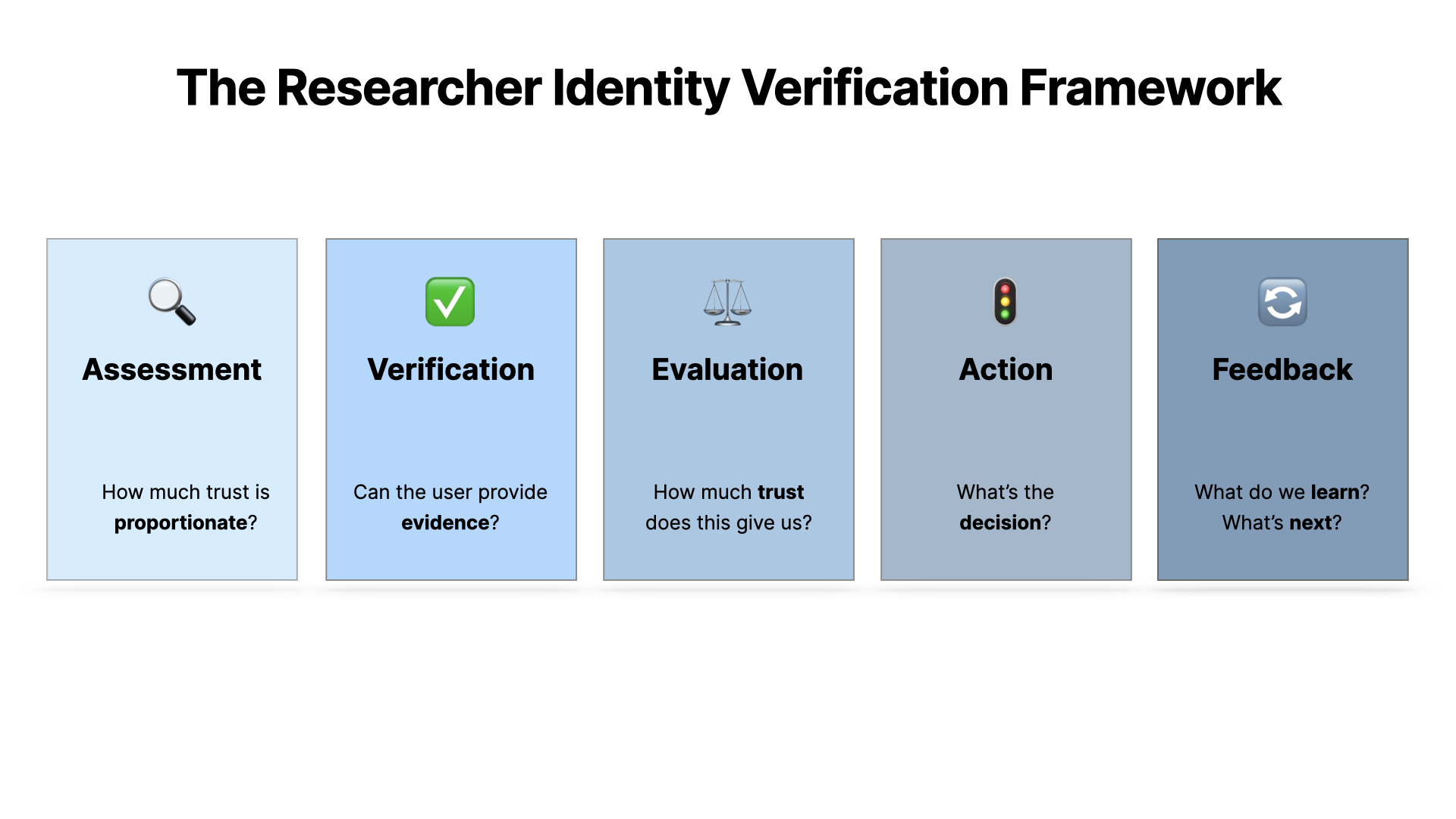

There are five parts.

-

Assessment - which is about deciding what\s proportionate in each case

-

Verification - which is about getting information from the user

-

Evaluation - which is about working out what this information means

-

Action - which is about deciding whether the trust is enough

-

Feedback - which is about making sure we're learning and adapting as we go along, because this is an evolutionary process not a silver bullet

Let’s go through these… starting with the first one.

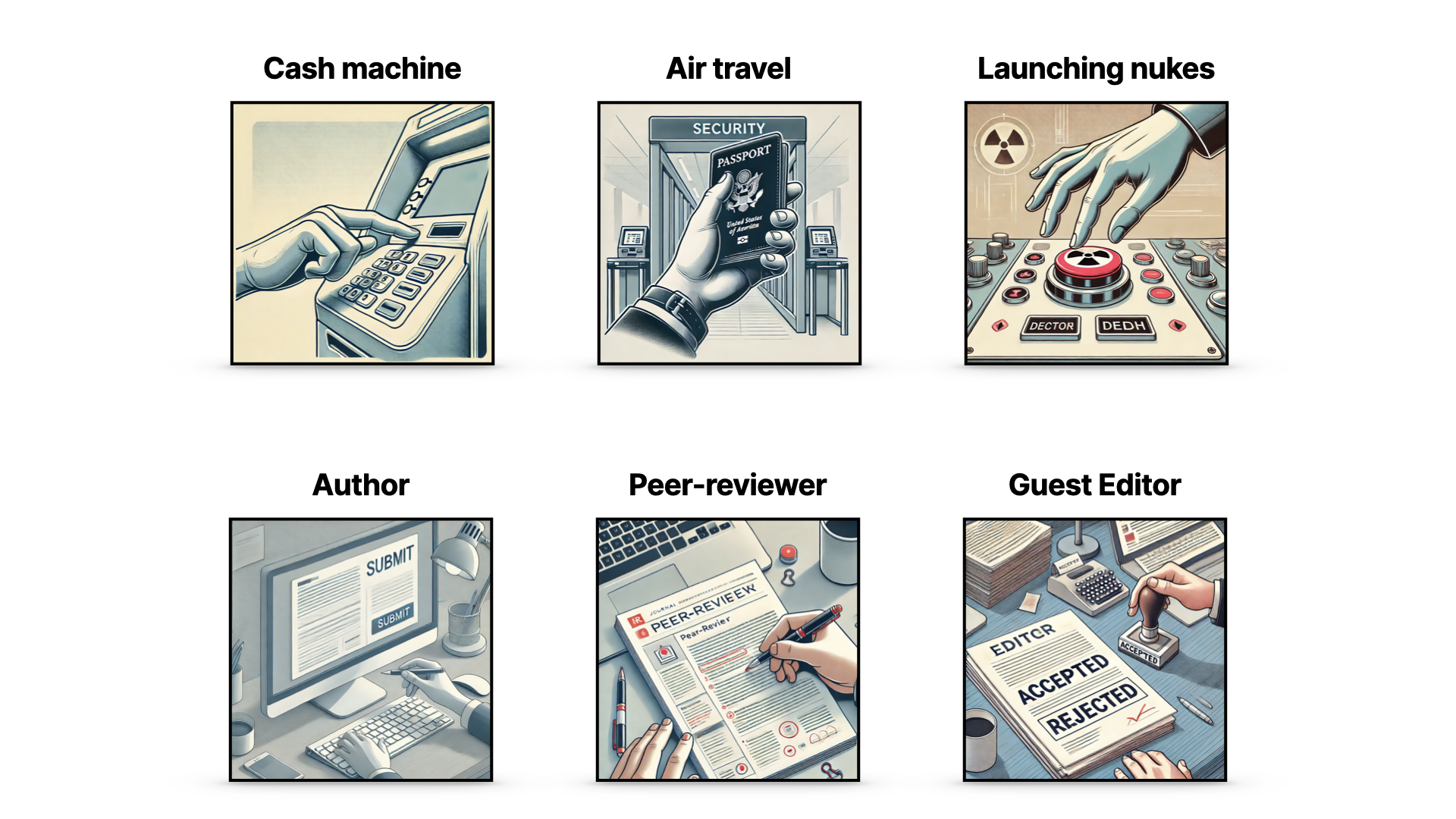

Not all actions in the real world present the same level of risk.

Getting money out of a cash machine requires a PIN and a card…

Which is less effort than boarding an aeroplane, because that’s a risker action

And this is less risky than launching the nukes, so that would (we’d hope) require a lot more verification.

Likewise, in academic systems, there are different levels of risk: this depends on lots of things, including what the user is trying to do. An author has less decision-making power than a reviewer, who has less than a guest editor, so you might expect more verification to be needed in each case.

But there are lots of other factors, like how much fraud an individual journal is experiencing, how much risk is tolerated… and this is an individual decision.

It’s really important to stress that this assessment step, the question of how much trust is needed, is a decision for the journal itself, the editor, the owner of the system. It’s a judgment for them to make, and that’s how this framework works.

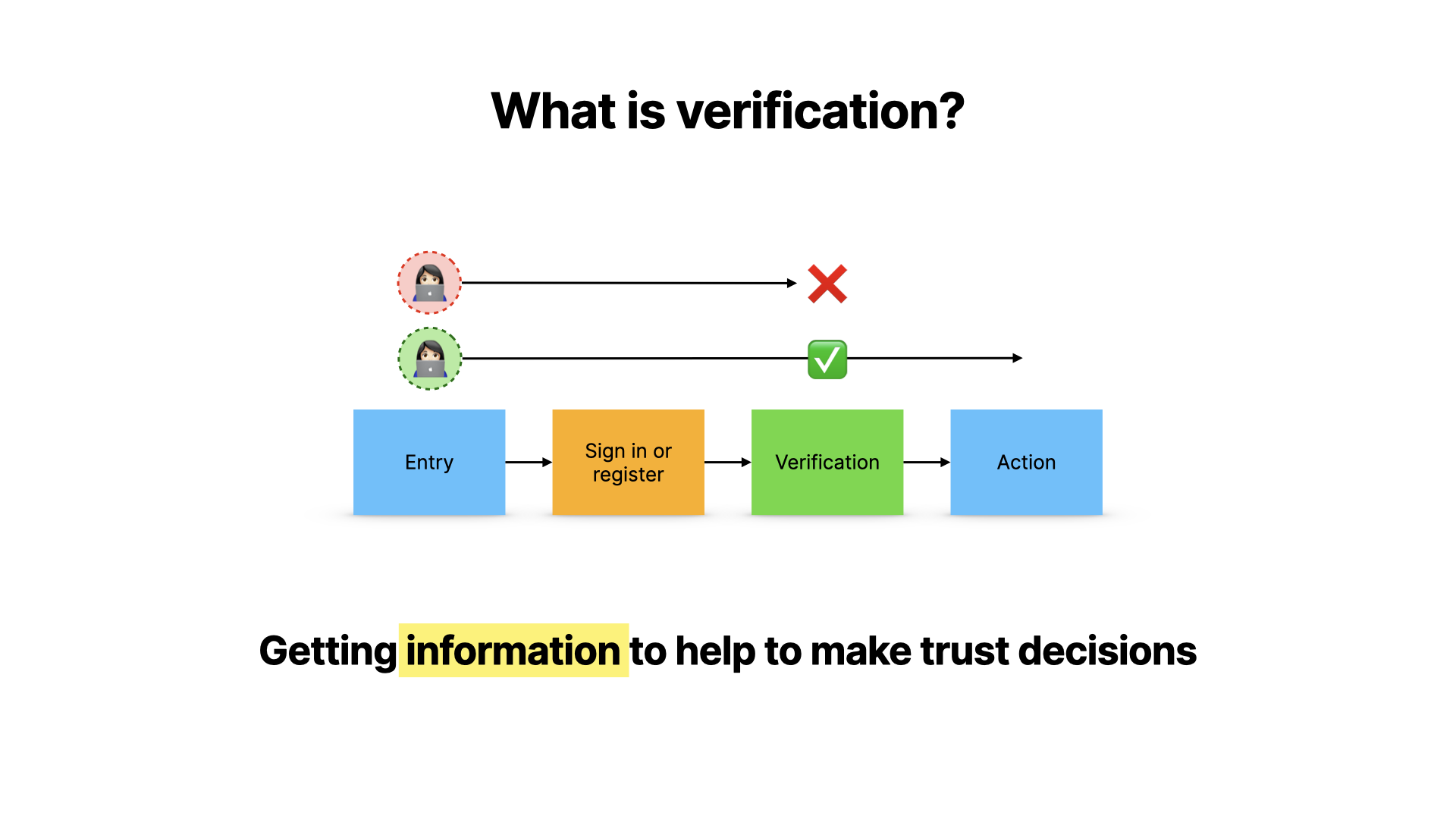

The next question is about verification itself.

Verification is about getting just the right information from users to meet the threshold of trust from the first step.

But what information do we want?

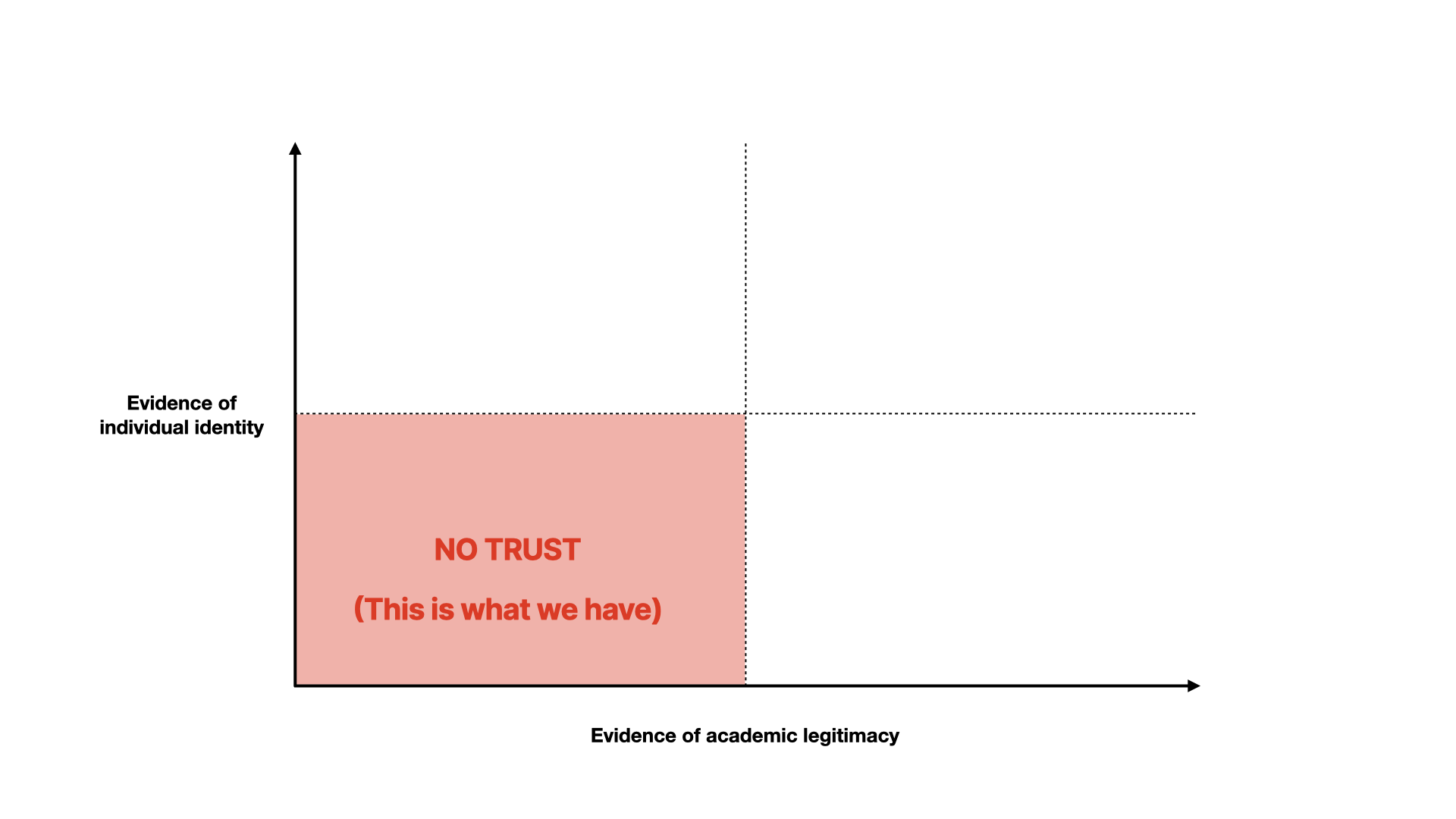

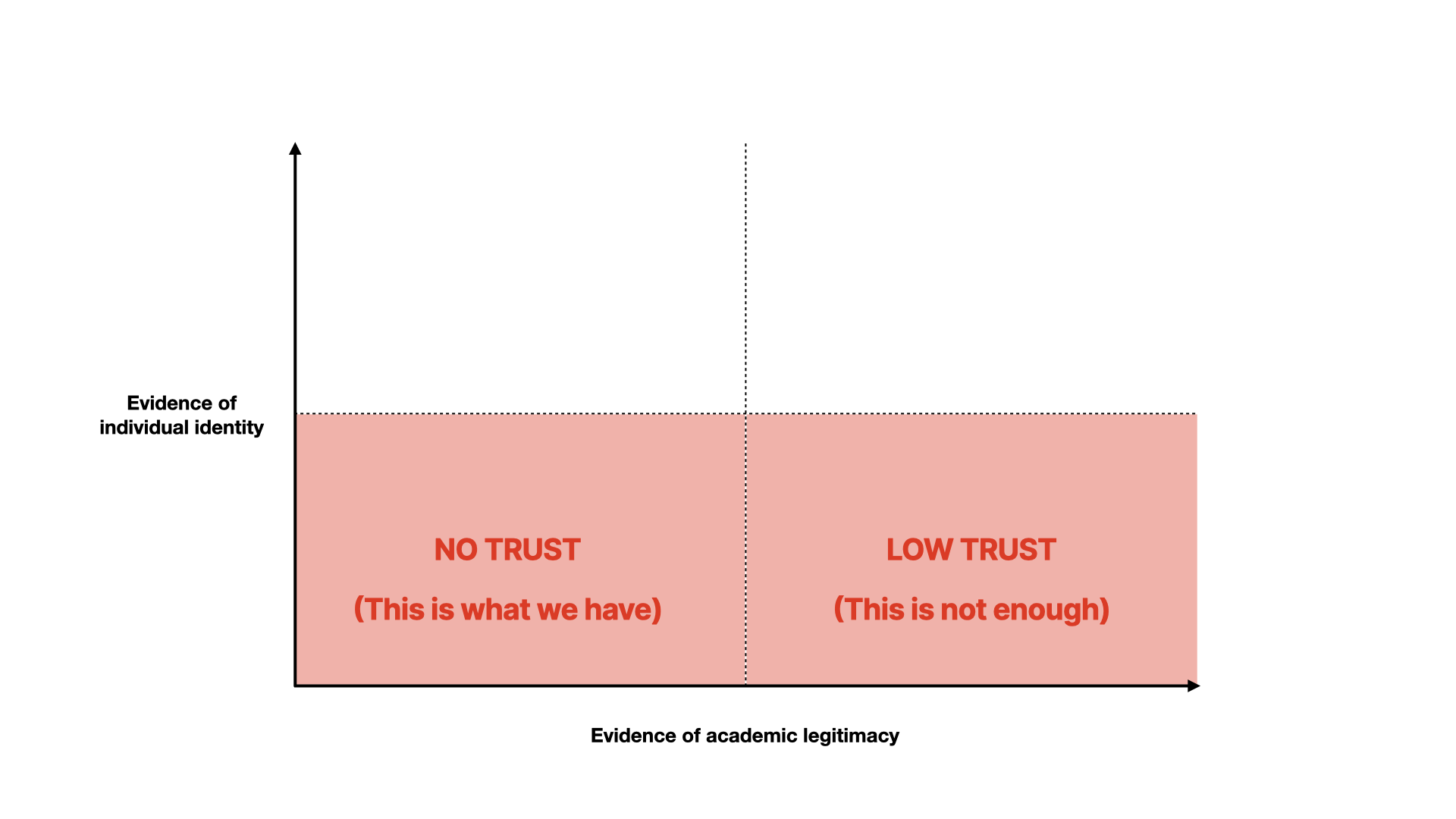

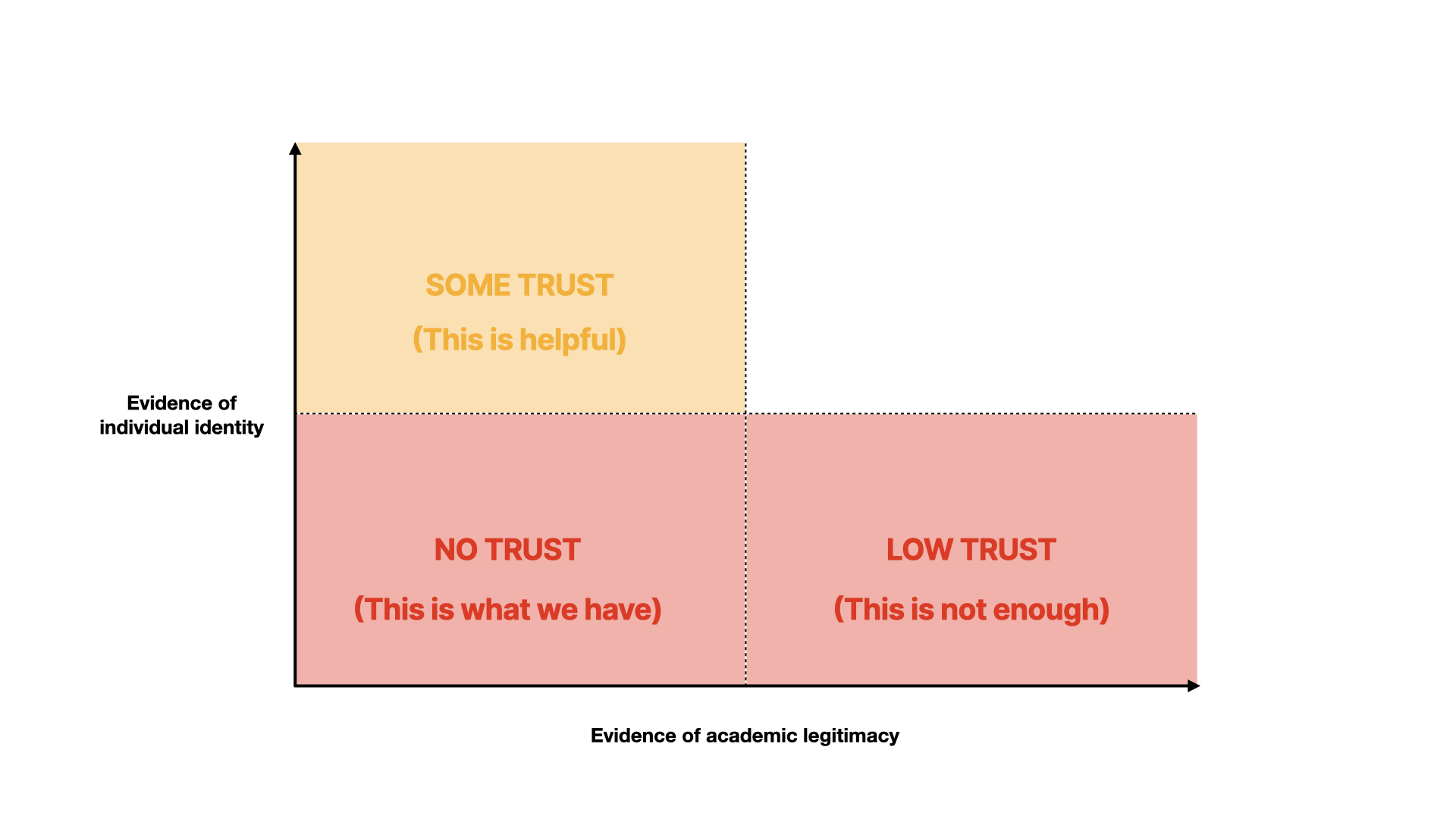

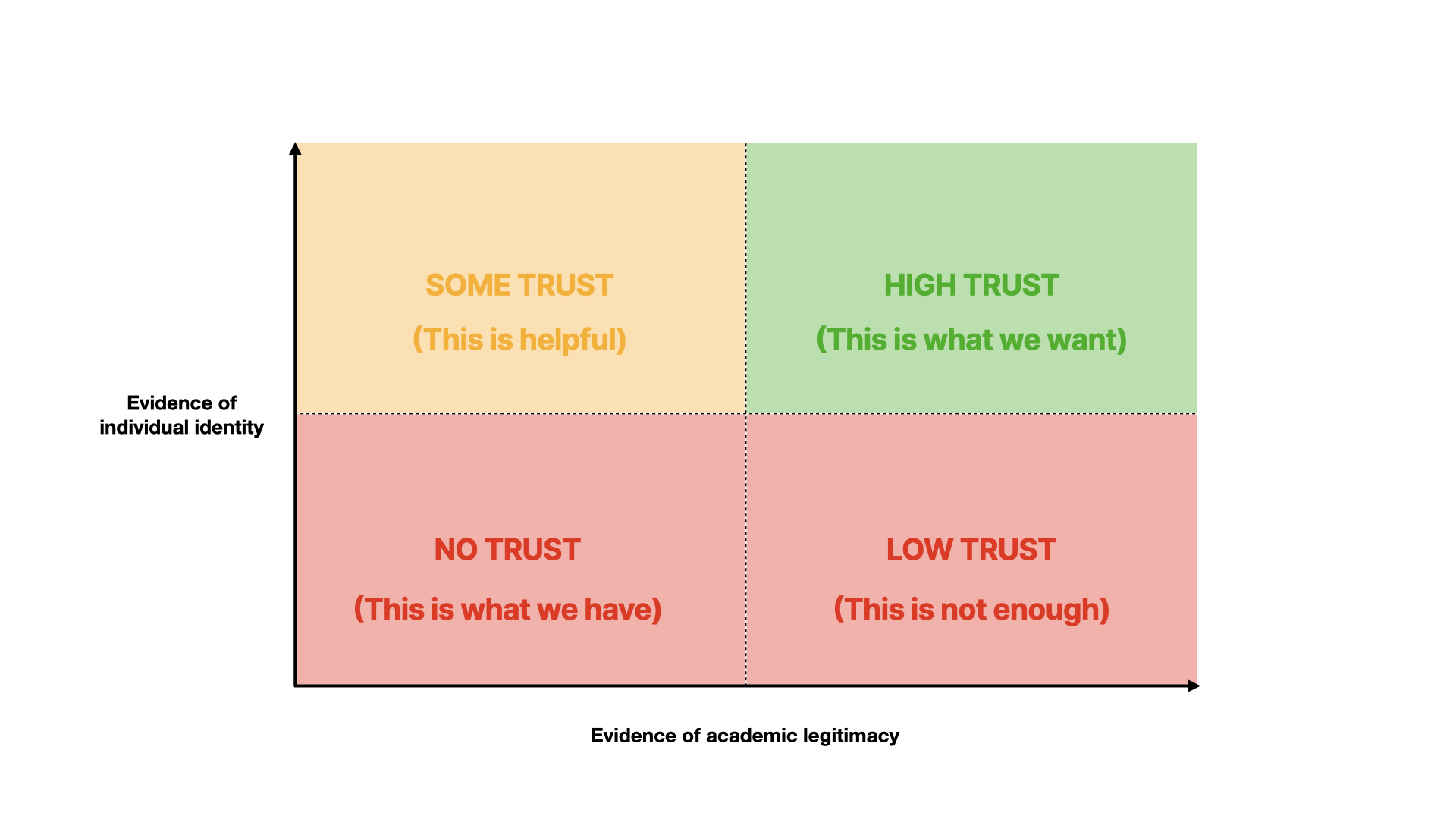

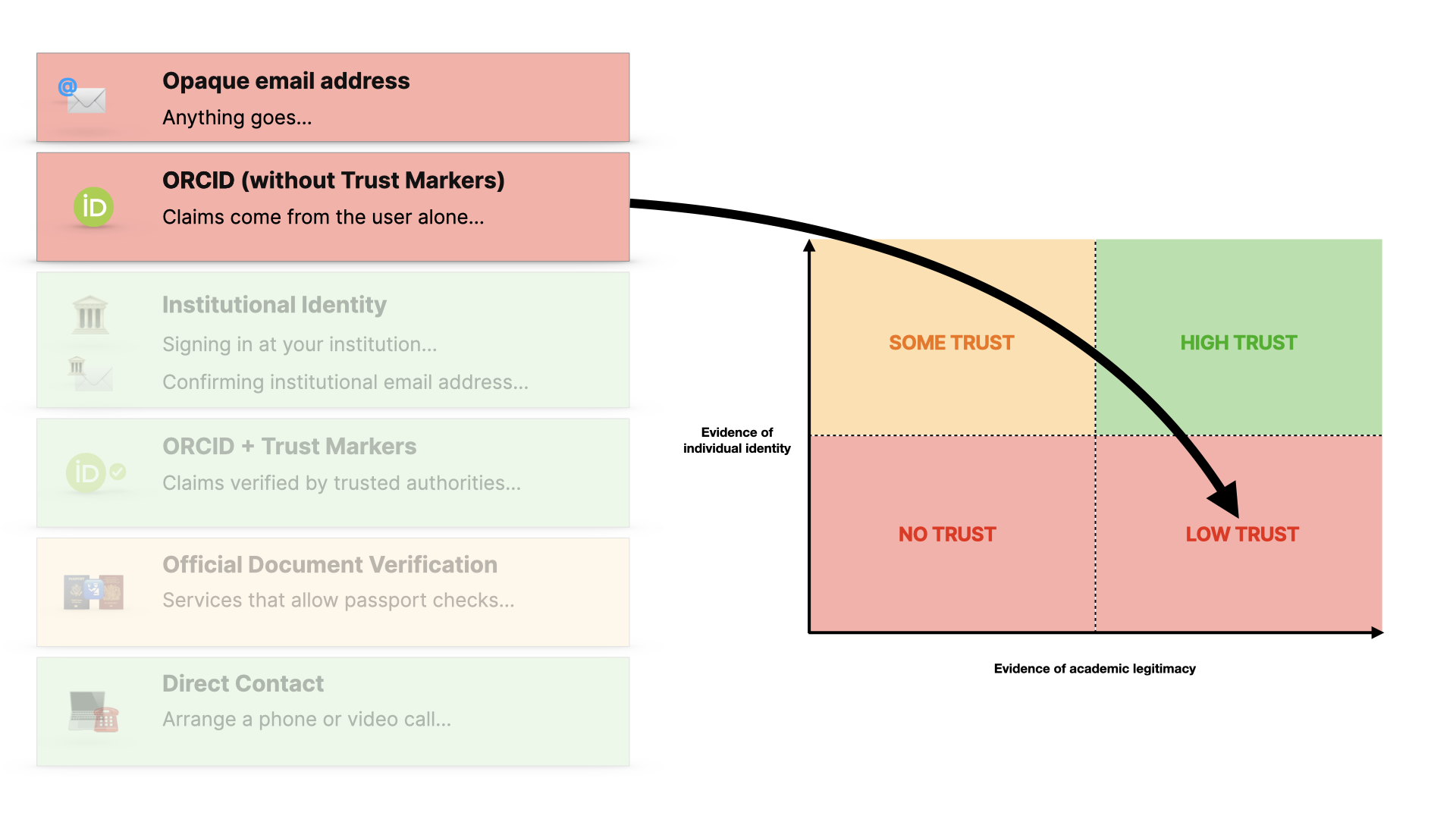

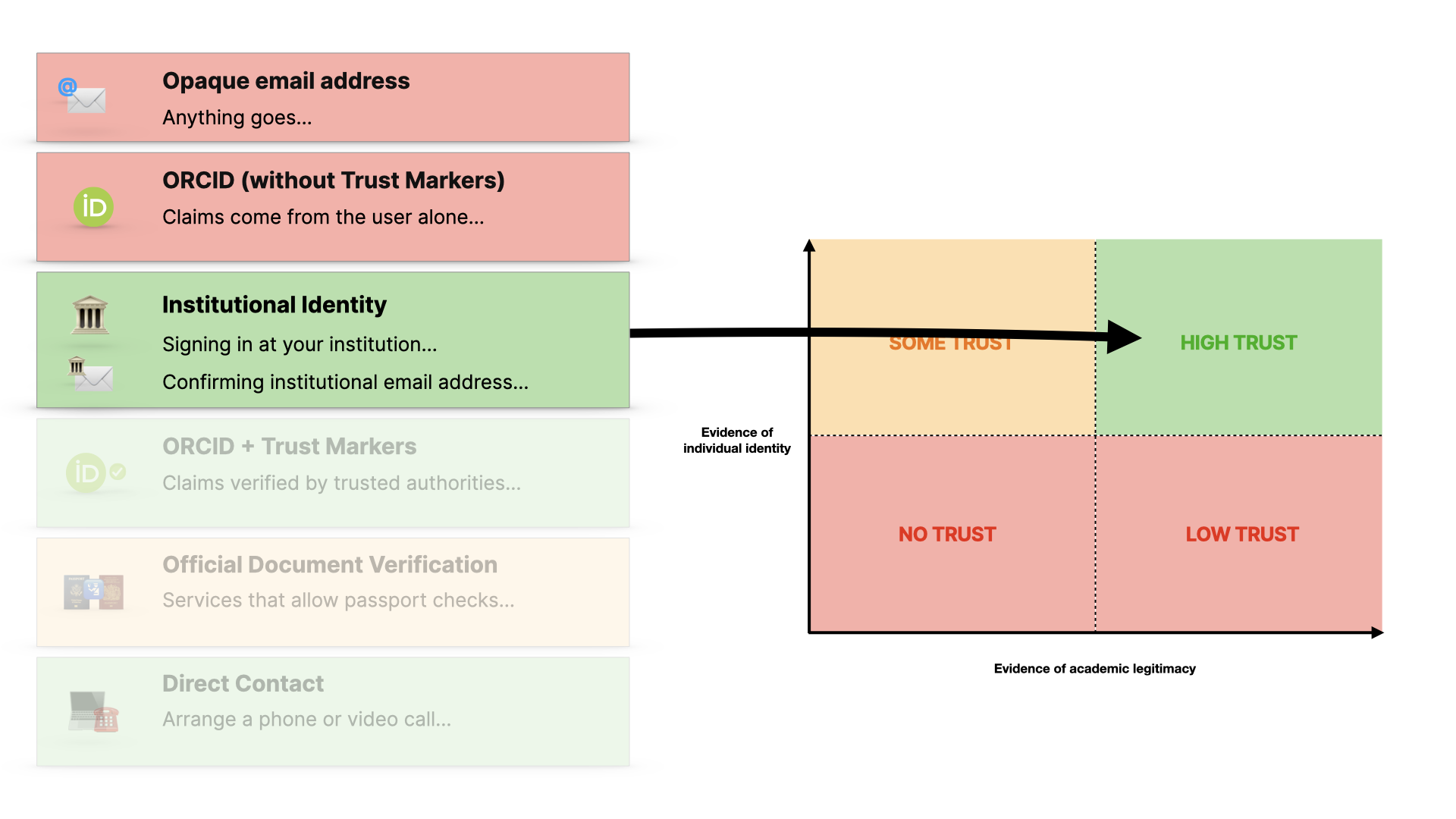

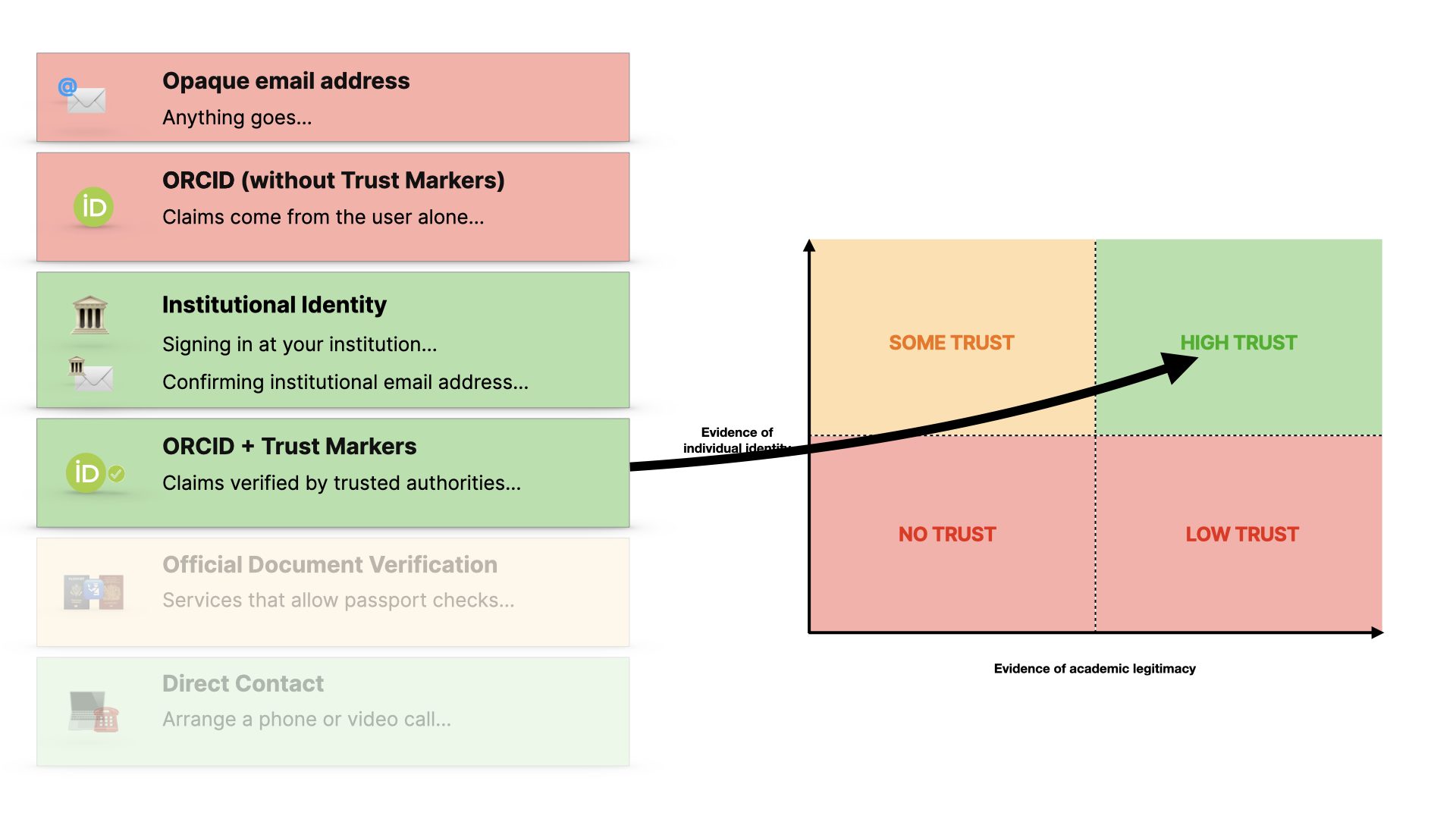

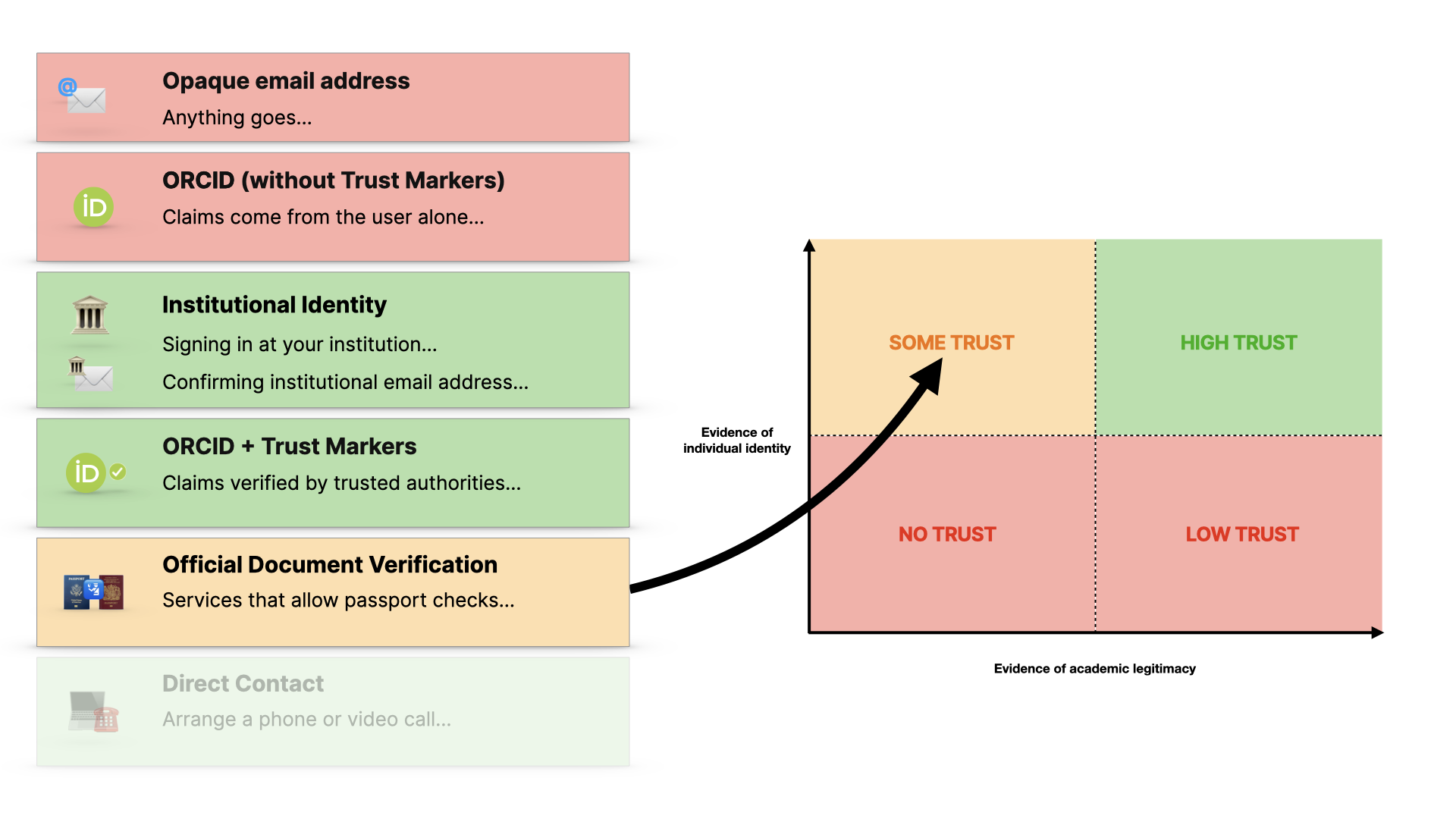

Here we break things down into two axes - evidence of individual identity and confidence we can have based on evidence of the person’s background.

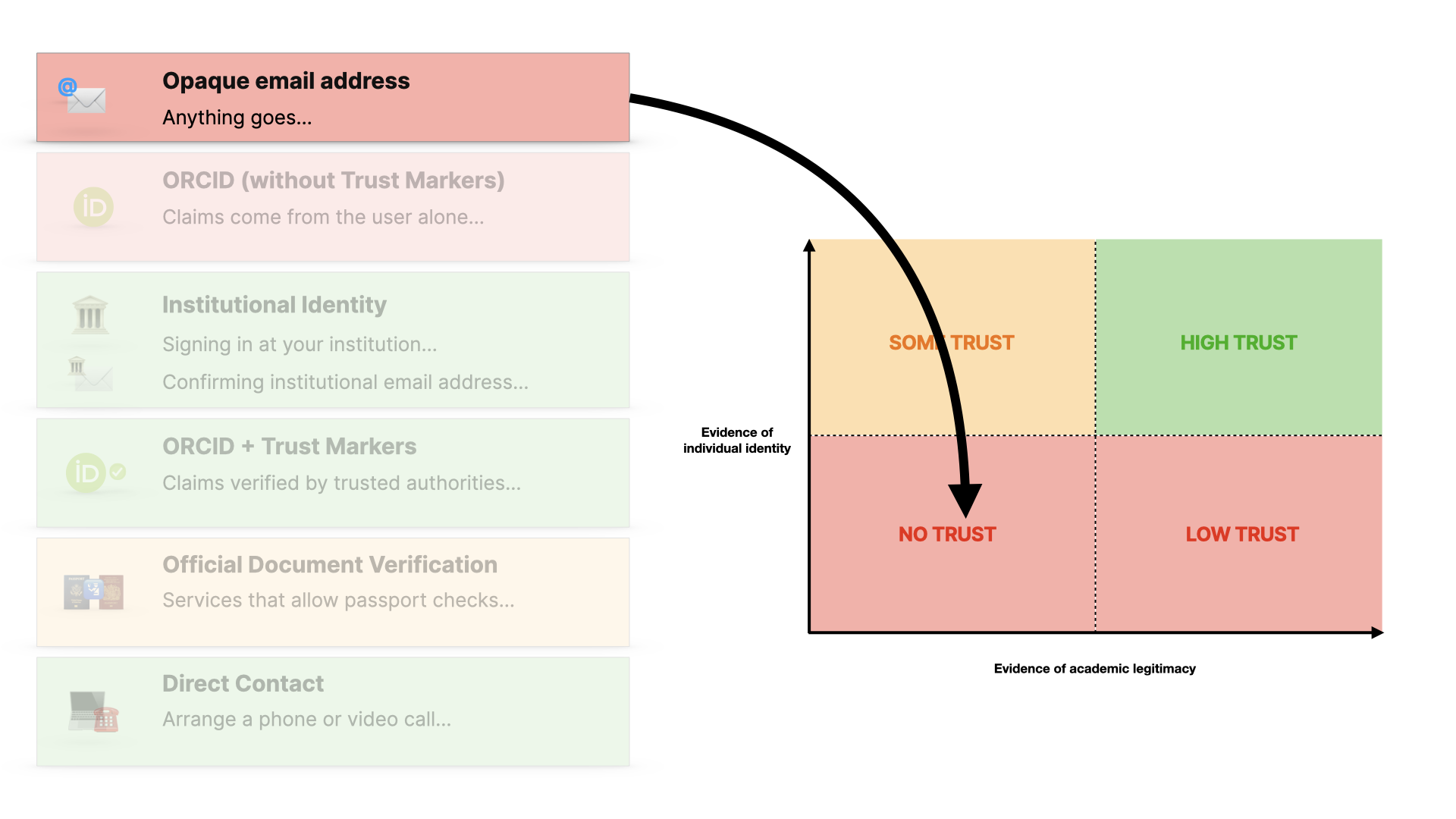

If we have little evidence of either - which is what a personal email address gives us - then we have no basis for trust.

If someone provides lots of self-made claims about their work, then this is also not enough to provide trust.

If we can verify their individual identity more, then we have a route to accountability, but we don’t have much evidence that they’re a genuine researcher… so this is better, but not the best we can get.

If we can get a combination of both: verified evidence about them and their work, then we have a way to trust them more.

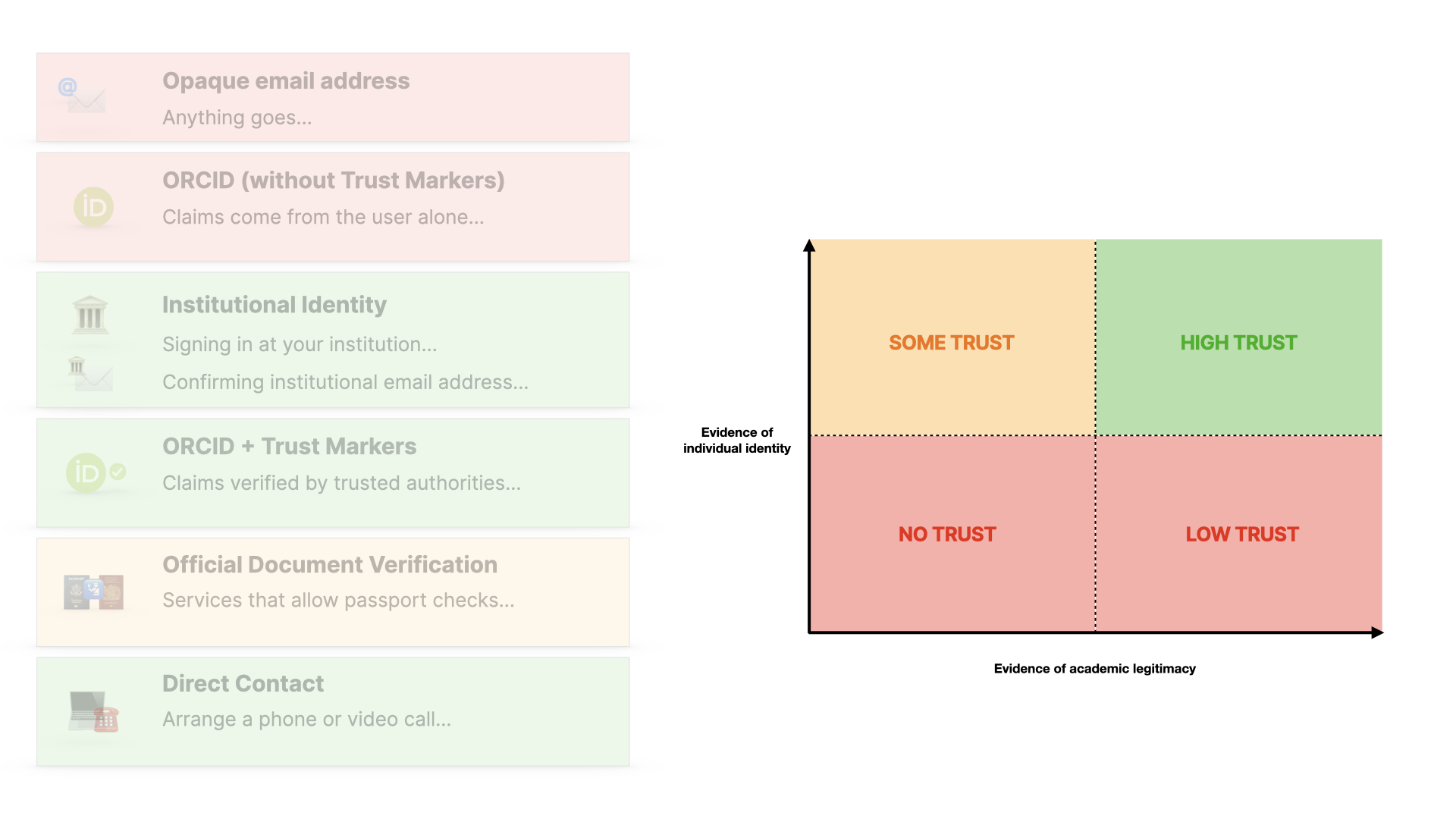

The framework then goes through a menu of options: Each has trade-offs, and different users will have different abilities to use each of them, which is a crucial point.

Email addresses as we know are here, with no trust

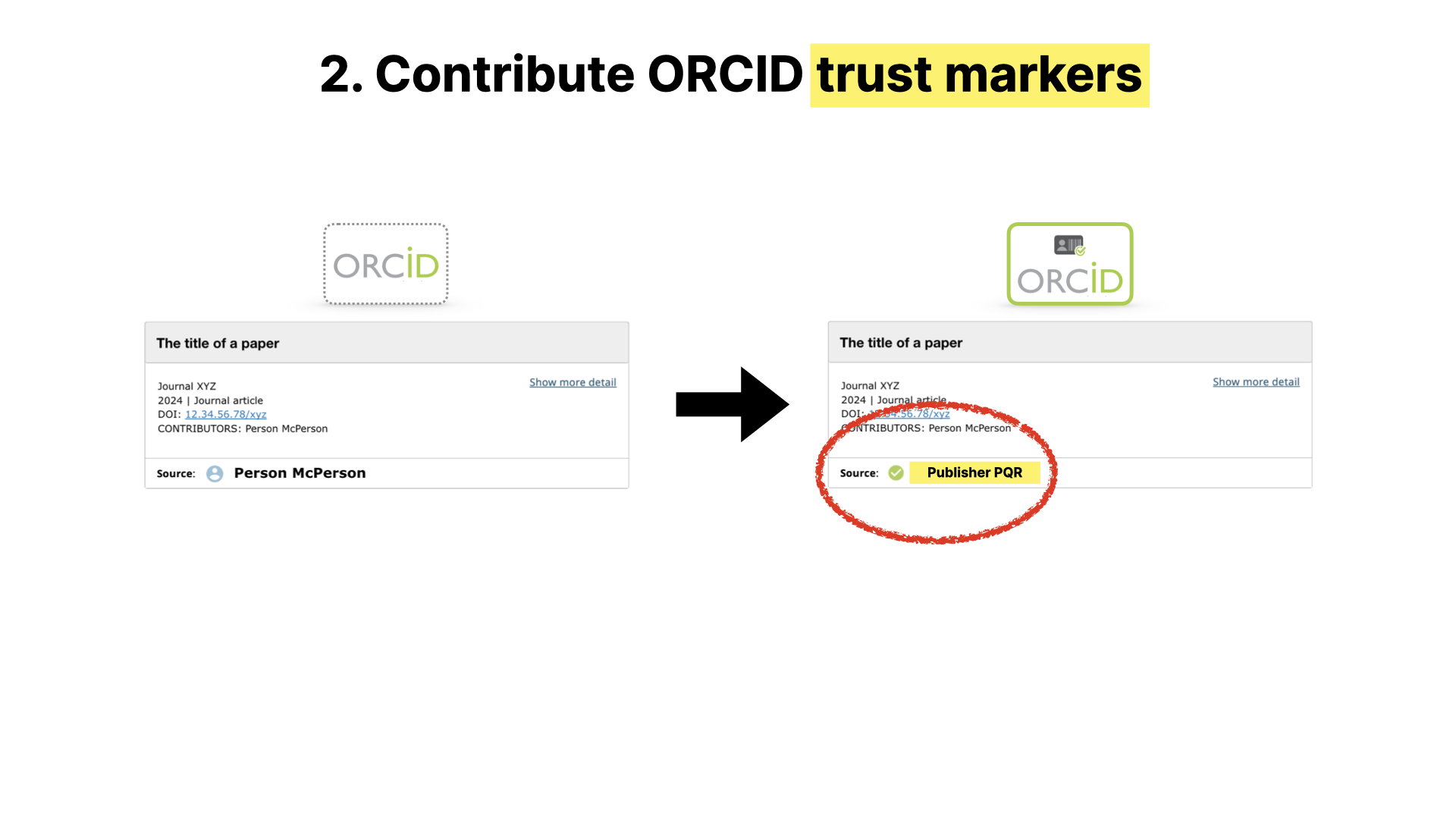

ORCID without external verification (in the form of trust markers) is better, but still open to manipulation.

Institutional identity, via federated infrastructure or email confirmation - gives us more trust… and I’m simplifying here… but it gives us evidence of who they are and also that they have affiliation, which is information about their academic credibility.

ORCID with trust markers - where the claims made in your orcid record are verified by trusted organisations, rather than just you - are even better… and there’s a whole spectrum in there…

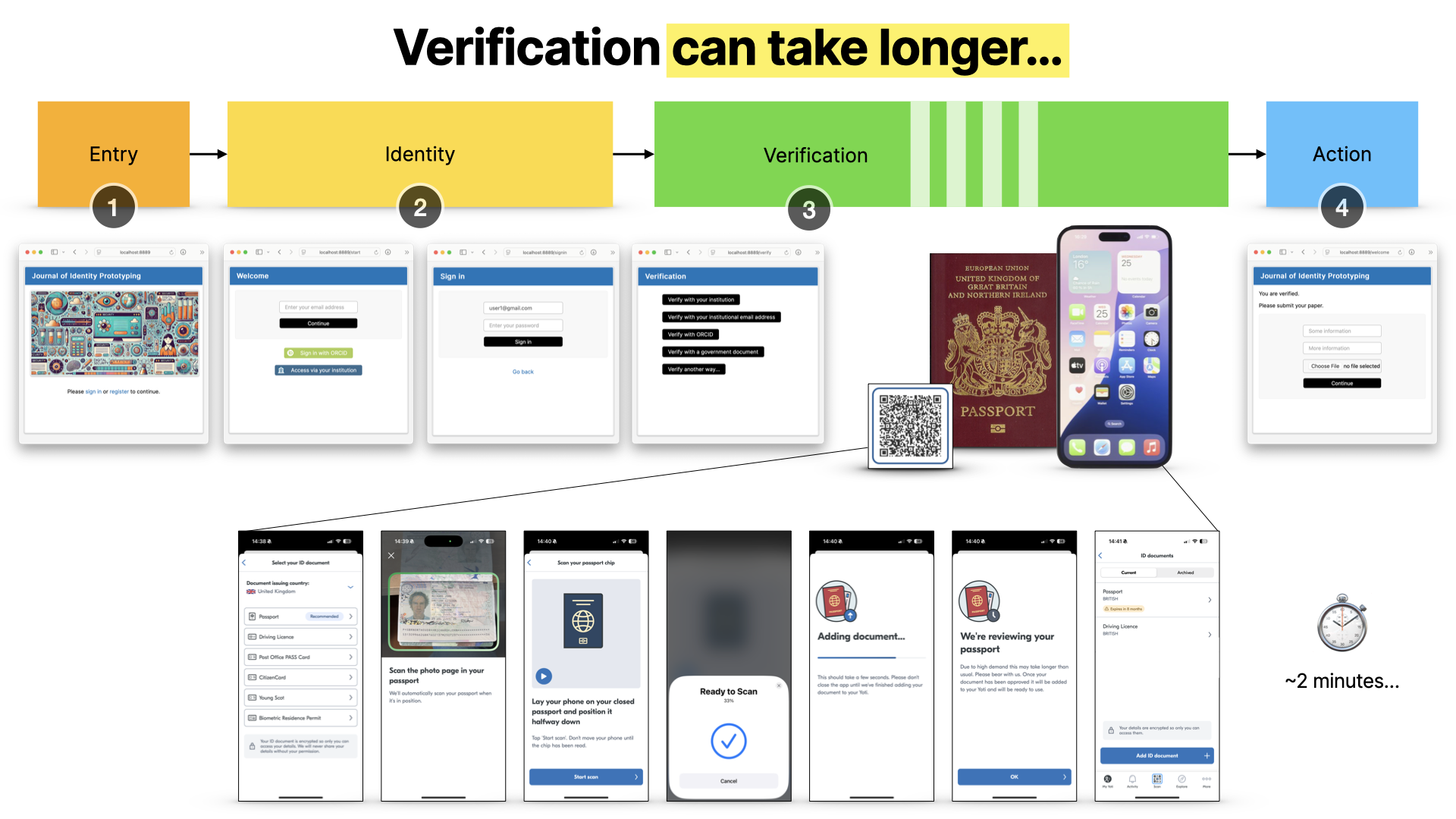

In the absence of those options, a user could fall back on an official document like a passport, which is what you’d use in AirBnB or on LinkedIn (if you want to have a verified account) and so on. We’re not talking about publishers handling passports and drivers licences, this is about using the same services that those platforms use.

And then finally, we’d need an ultimate fallback, where the user directly contacts the journal to arrange a zoom call or something… using the kinds of manual checks you’d use today if you needed to.

There are other options too, like vouching (where someone else, like a research supervisor, is linked to someone like an early career researcher… this is potentially more complex, but something we’re exploring)

But the main point is that there’s this range of options, to make sure that nobody is excluded.

And the point is that none of these is a brand new idea… we’re working off systems that already exist, or in the case of trust markers (whether that’s through ORCID or an equivalent of ORCID) could be encouraged more and built upon.

We then have verification slowing down or stopping people from submitting work or taking part in peer review if they can’t at least provide some evidence.

And if they can, then they can go ahead.

And if they are verified, but still go on to commit fraud… then like a speeding driver, there’s accountability. This is the feedback loop I talked about.

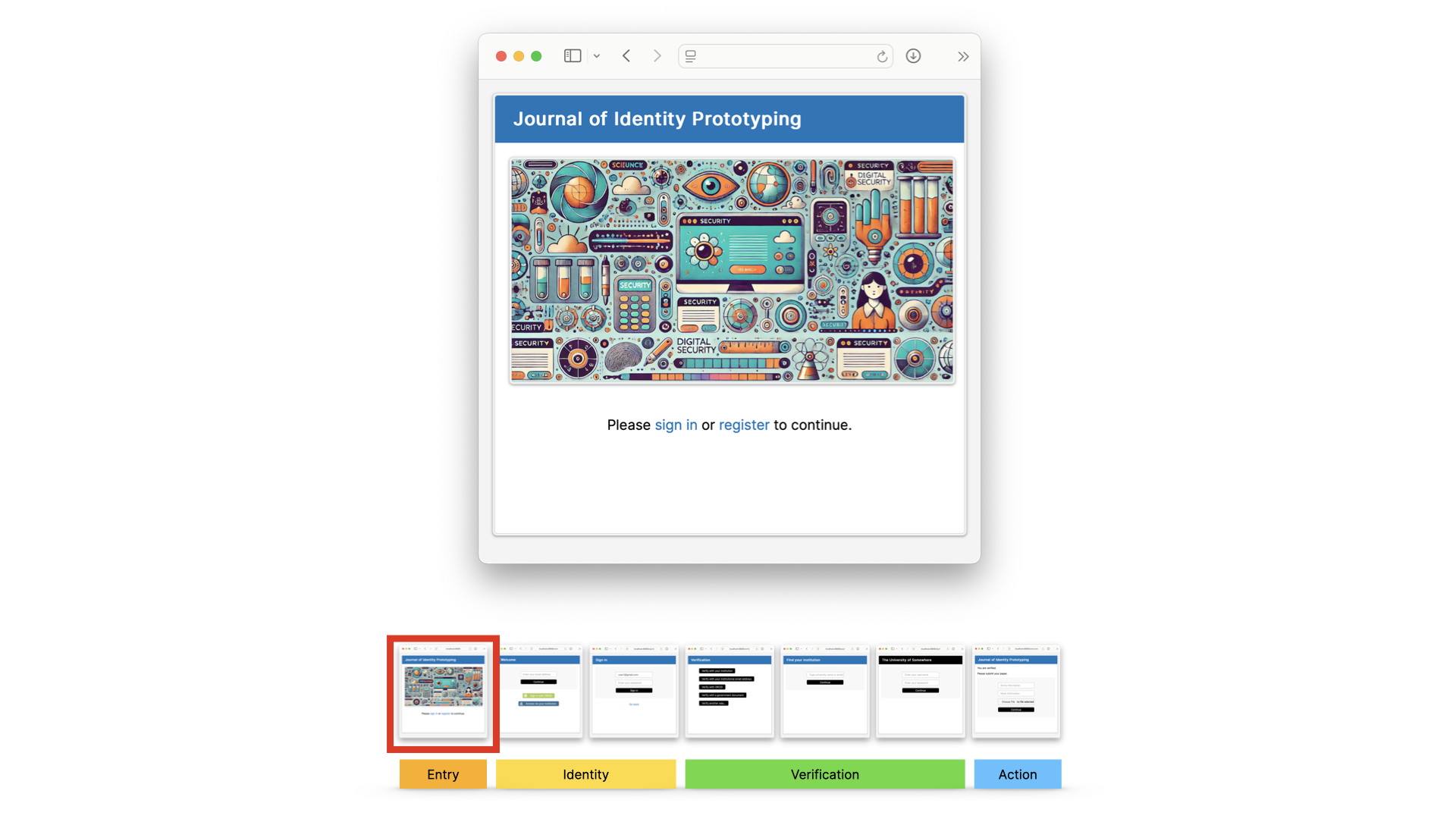

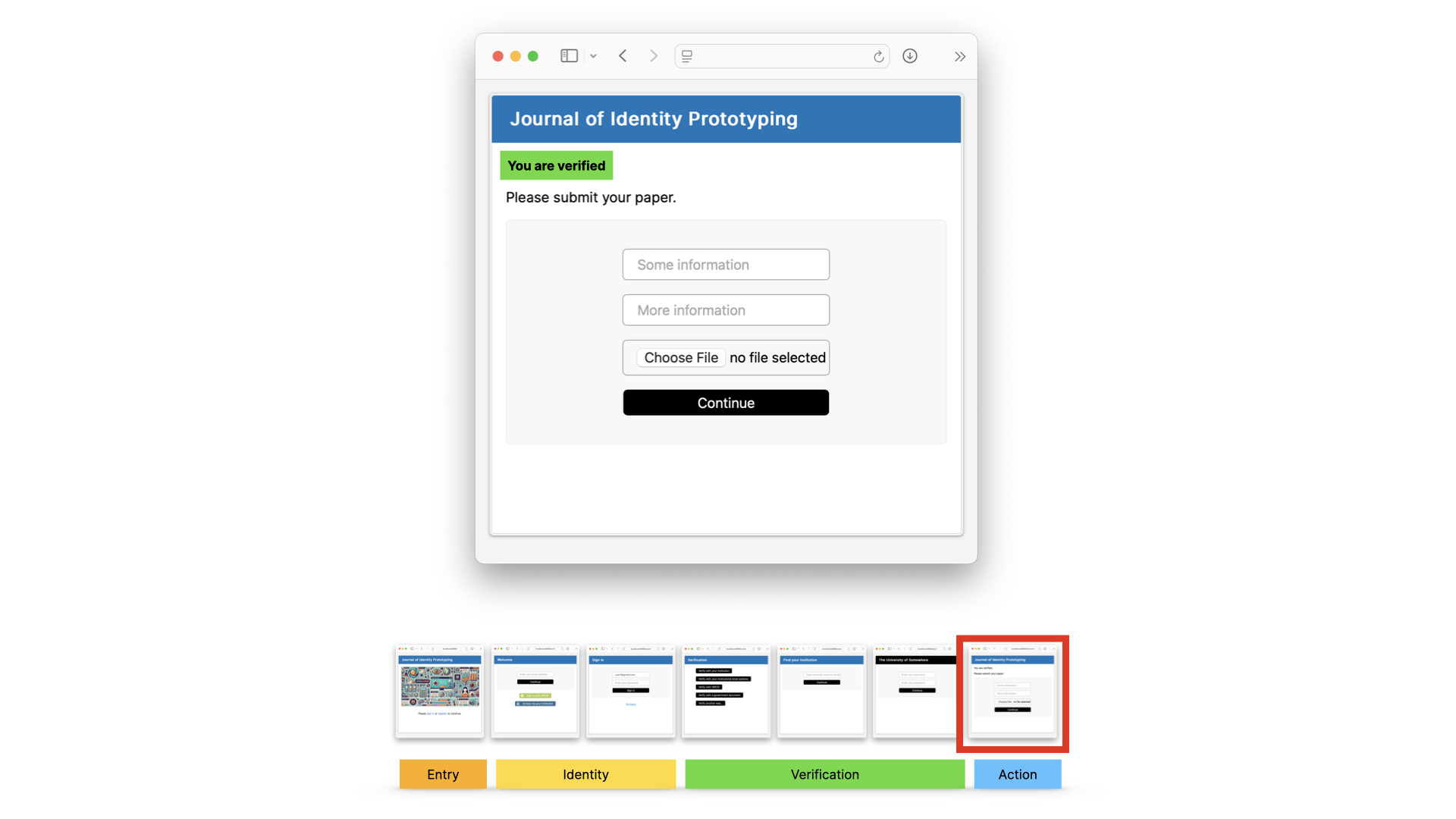

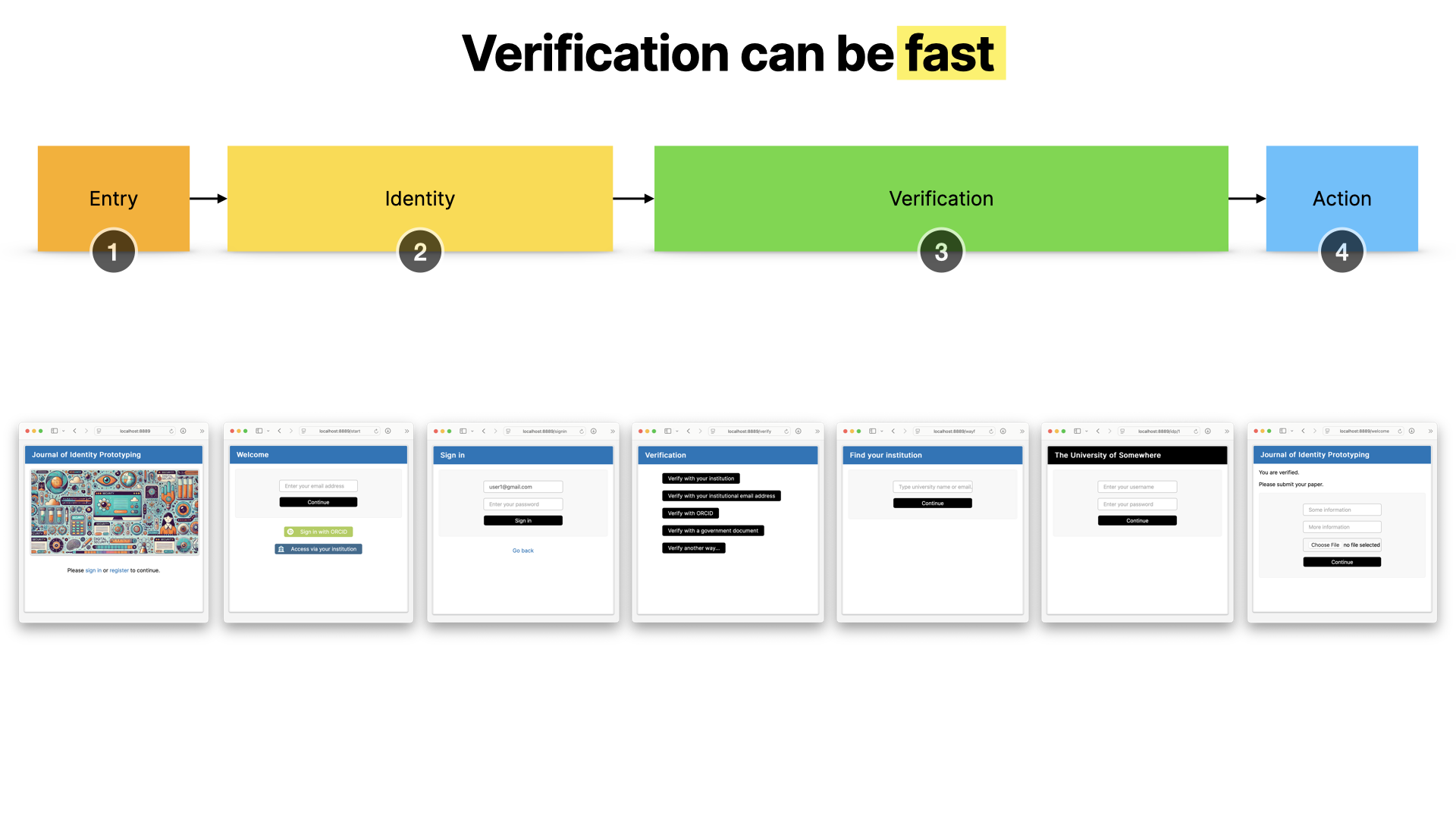

Let’s have a quick look at how it could work. This is just a mock-up - we’re doing some UX research into the actual user journeys, so bear that in mind… this is just an illustration.

Someone might arrive at a journal - in this case the journal of identity prototyping - and sign in.

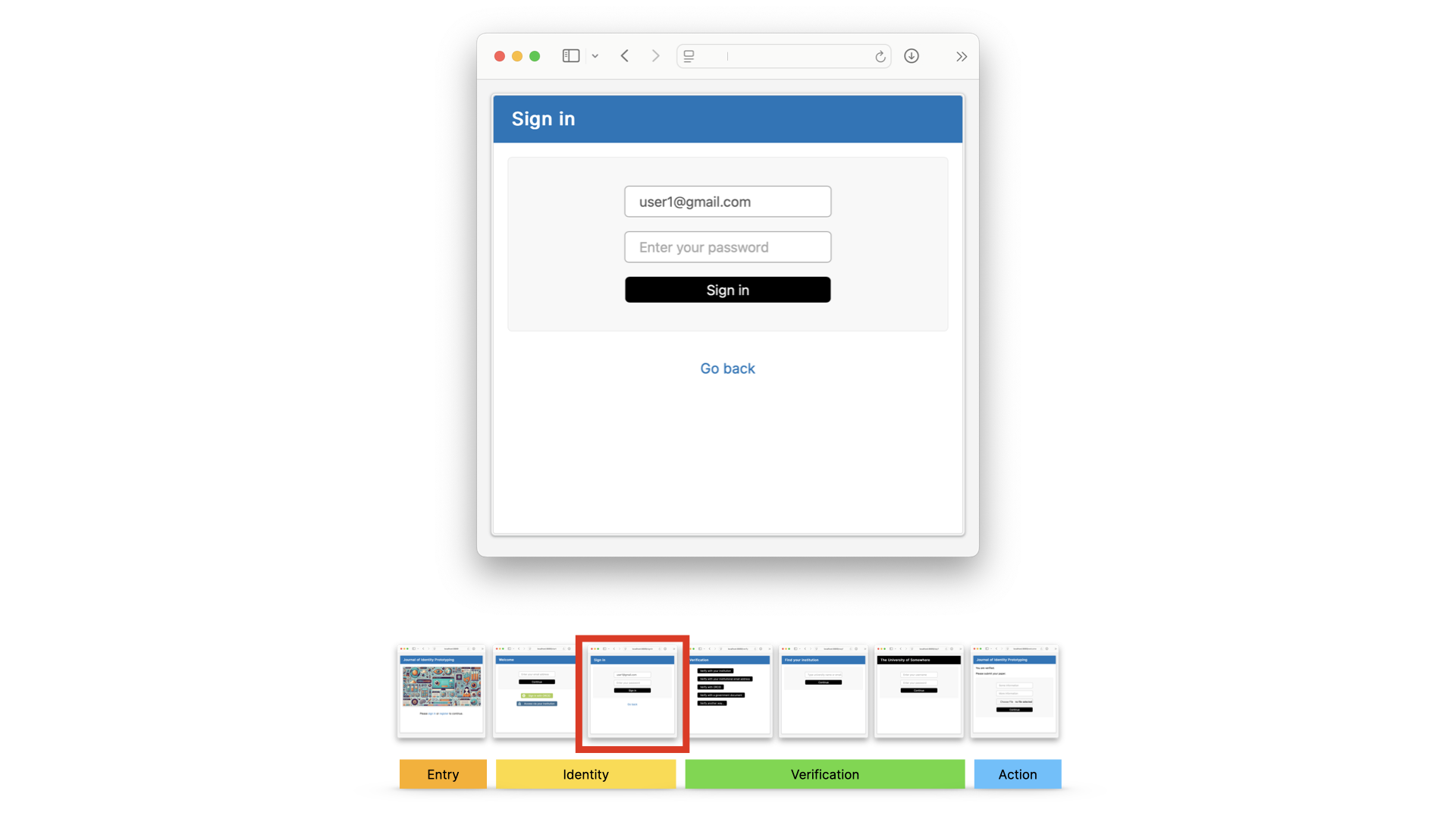

Let’s say they use their personal email address, because it’s convenient, and we’re not saying that this isn’t allowed. It’s just not enough.

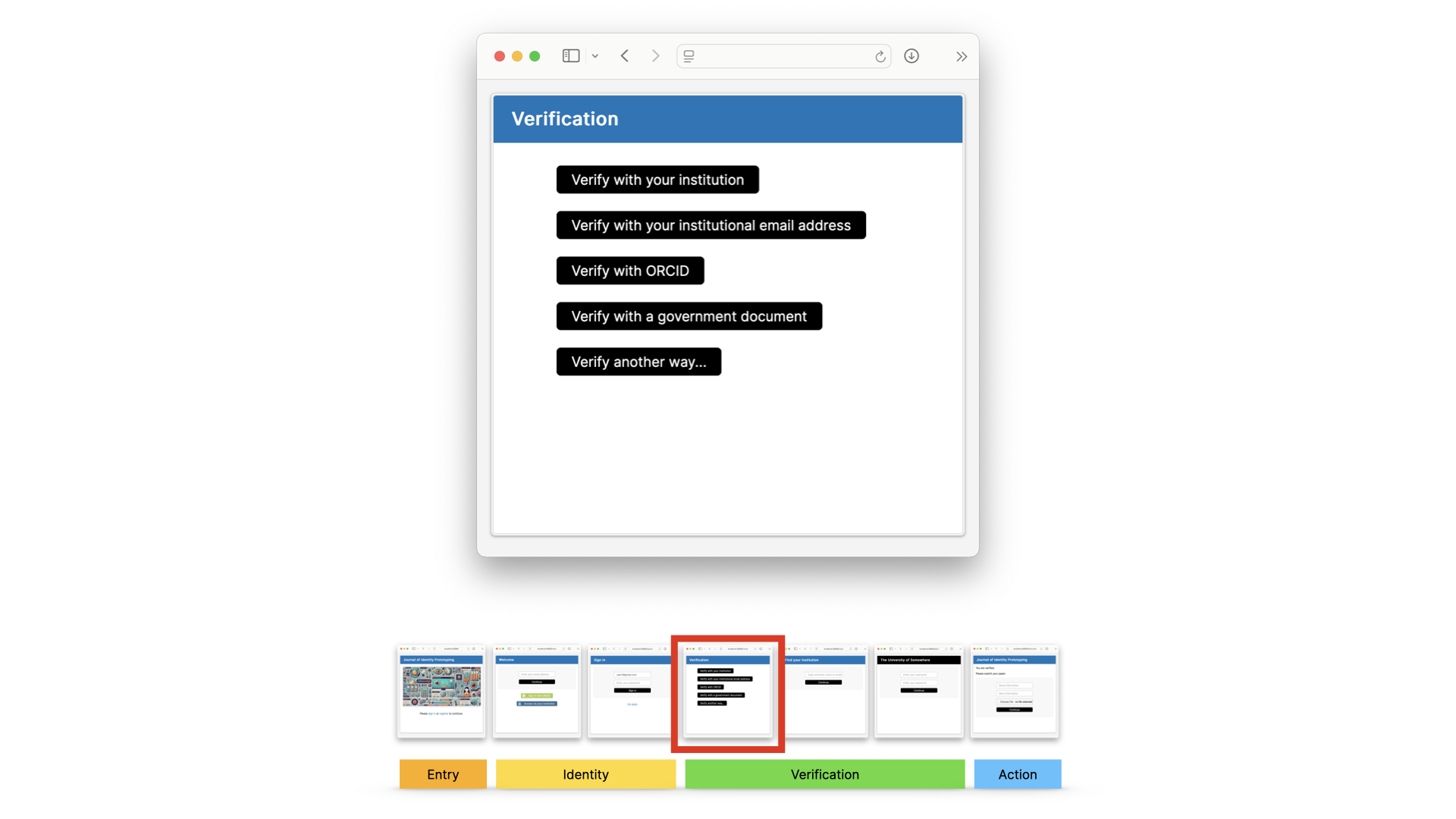

Next, there would need to be some kind of choice: how do you want to verify yourself?

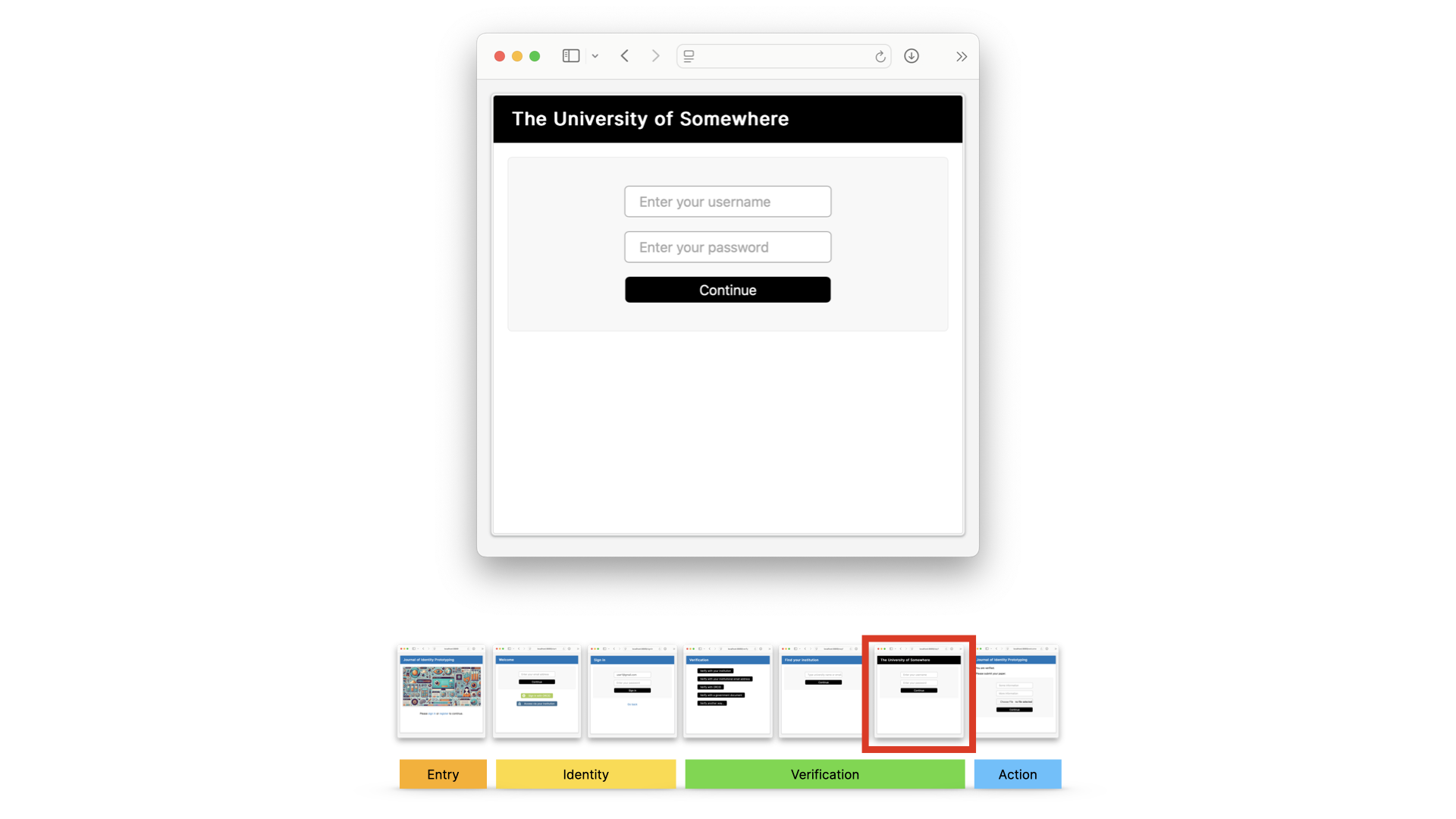

Let’s say they choose to use federated identity. They go to the WAYF screen, as they would today in an access user journey.

They’d be sent to their institution to sign in… and their institution would send back proof of their individual identity and their institutional affiliation, and because there’s a trust relationship there, the information is trusted.

And then they’d return, and they’re verified, and can keep going.

This is reasonably fast.

But it could be really fast, if the user just signed in directly with their institution or with ORCID, or used their institutional email from the very start.

In cases where they don’t have an institution to refer to, or even an ORCID record, they could use third party document systems, as they would with other platforms. They’d only need to set this up once, remember, then they could use this much faster next time.

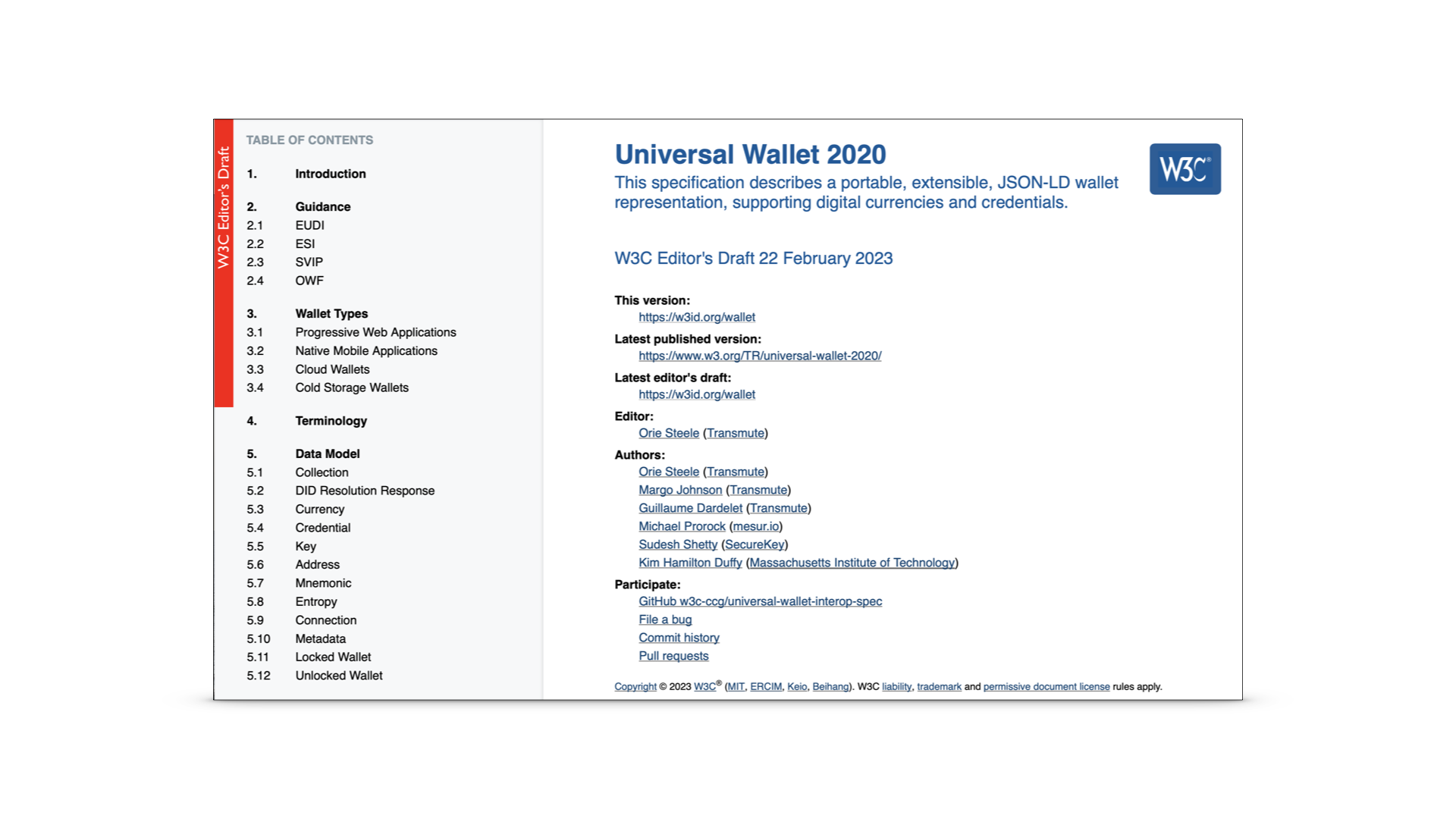

Now, I’m just going to touch on a very important point, which is this is where digital wallets come in. This is exactly the use case for them… where you carry around verified information about yourself and can use it in secure and private ways. We’re going to be working more on this, but I thought I’d just mention them here, as they’re the direction that all of this is heading in.

So the report we’ve produced about this framework discusses all of this, and has a set of recommendations. I’m just going to call out the main ones.

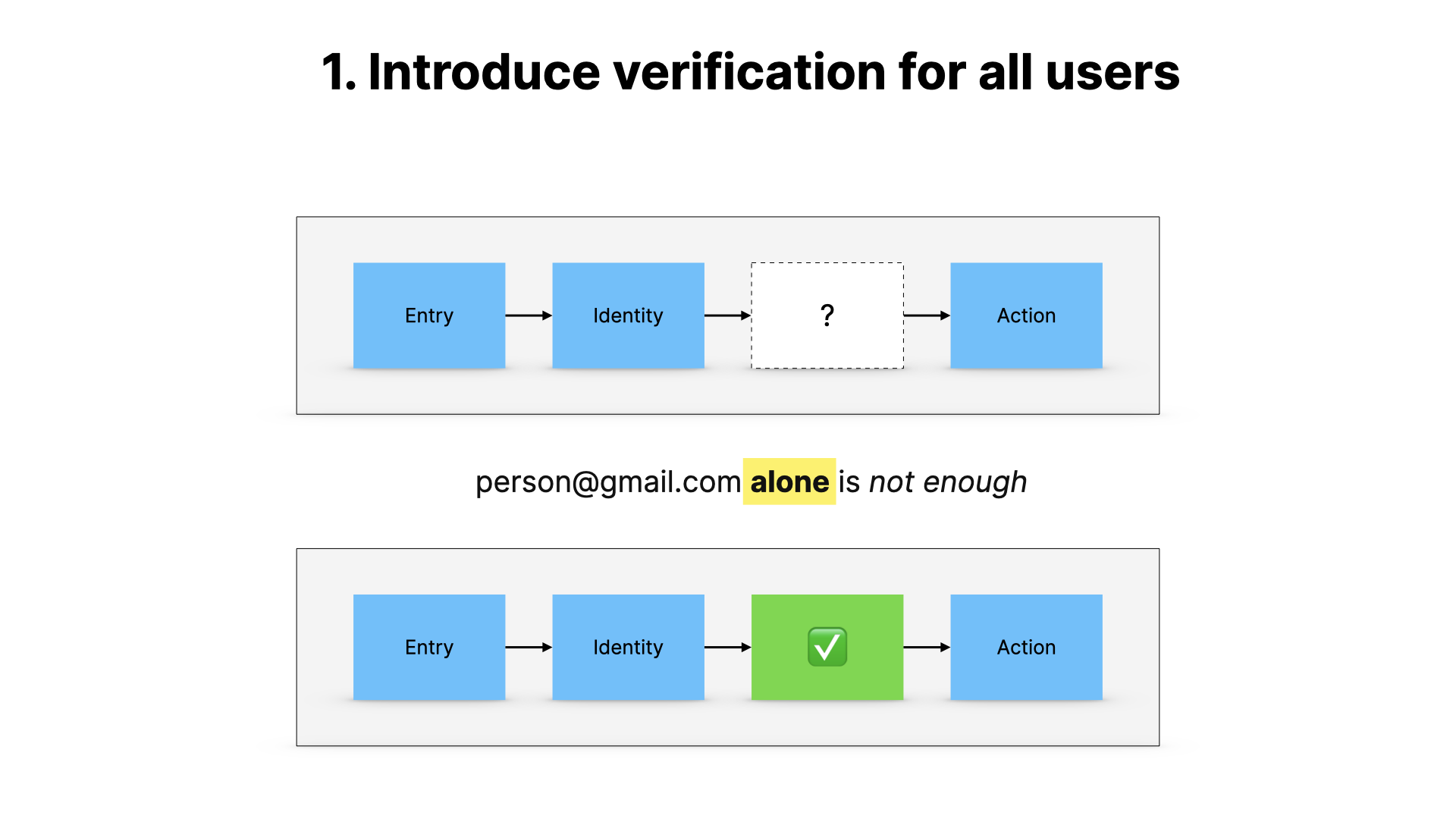

The most important one, as you know by now, is to introduce verification, and to stop relying on unverifiable identities. This is in the context of everything I’ve talked about today.

The next recommendation I want to mention is to use ORCID trust markers. As many of you will know, this is where a trusted external entity verifies the claims that are made in an ORCID record, rather than them being purely self-claimed.

The more publishers, funders, academic institutions and so on add trust markers into the system, the more powerful and useful this becomes.

And although this is an ORCID presentation, I think ORCID themselves would be the first to say that this isn’t about ORCID. If there are equivalent open systems that operate in the same way, and come up with ways for verification to be interoperable, then all the better.

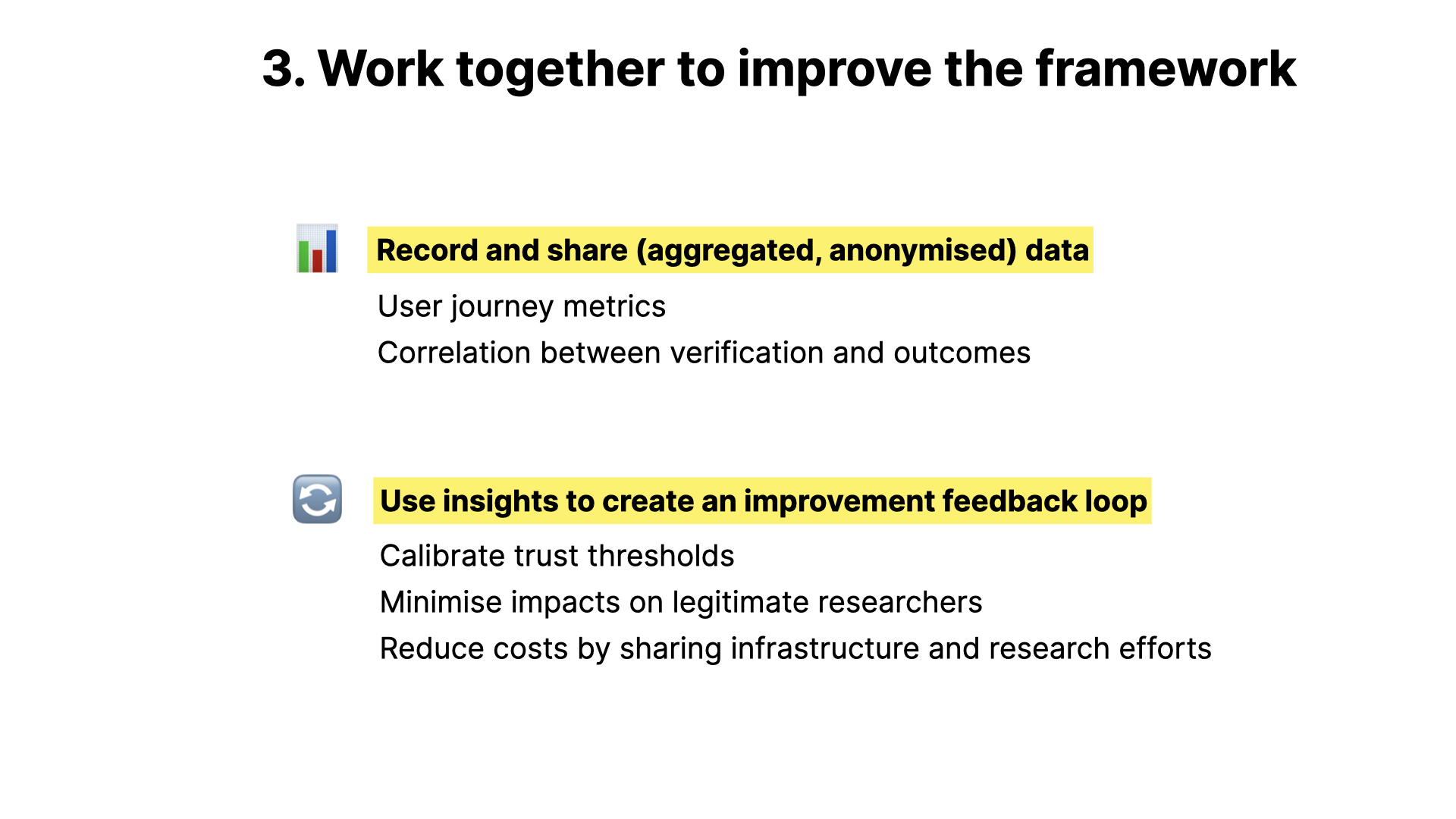

The final recommendation I want to mention is a broader one, and that’s to work together to make this a collaborative effort, rather than a closed one. This is like science, where we share our ideas and build on them. There’s a lot of work to be done here, and it’s only going to work if it’s done in this open way.

Finally, I want to talk about some of the challenges here.

- This isn't a silver bullet. Like most things in life, there are trade-offs, and we have to work hard to understand and balance them

- We've got to do the research into how to make sure the principles I mentioned earlier are lived up to, and designed in from the start

- How would this actually be implemented by editorial platforms of different kinds, not just the big ones?

- How does assessment of risk and the thresholds for trust actually work?

And this is why our current and future work involves testing our assumptions, working to understand the challenges more and trying to work them out in the real world.

We need to be able to show that these ideas stand up, and to change course and improve things where they don’t.

So to conclude…

- This is not about barriers or gateways or identity for the sake of it.

- It's about building a system where communication, which is the foundation of research, can be trusted

- Verified identity is central to this, but it has to be done right.

- And it can only be done right if we communicate about it, and I hope you'll provide feedback